HFCs Beyond Cooling: Tackling Emissions in Fire Suppression, and Other Industries

Table of Contents

ToggleDeciphering the AIM Act: Unveiling the EPA’s Subsection H impact on fire suppression

An Overview of Recent Developments

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has recently enacted a comprehensive trilogy of regulatory amendments. Due to the extensive nature of these changes, we have decided to break down the updates into more digestible segments.

Today, we shift our lens to the role of HFCs in fire suppression systems. While the initial plan was to cover a broader spectrum, including flammable refrigerants, and although we planned to discuss the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act’s (RCRA) implications, certain items still need to be answered.

To ensure the integrity of our discussion, we’ve postponed our RCRA-focused insights in favor of a more factually grounded presentation. Nonetheless, today’s focus remains sharp on HFCs within fire suppression systems.

This regulatory wave marks the beginning of a new era for refrigerant management.

The EPA’s latest regulations under Subsection (h) call for a vital discussion about our methods for servicing, repairing, disposing of, and installing equipment. In this update, the EPA uses incentives and regulations to steer the industry.

The EPA and the equipment marketplace share a common goal: to ensure a sufficient supply of refrigerants for servicing high-GWP equipment throughout its expected lifespan.

HFC GWP Equivalency

| Material Type | GWP (AR4) |

|---|---|

| R-227 | 3,220.00 |

| R-236 | 9,810.00 |

| R-23 | 14,800.00 |

| R-125 | 3,200.00 |

🧑🏻💻 Register Now for Our Free Webinar

Don’t let outdated budgeting models put your operations at risk. Join industry experts as we break down how current and future HVAC/R regulations can drastically impact your capital planning.

These regulations are extensive and multifaceted. To fully understand the EPA’s rationale, expectations, and proposed directives, it is essential to consider a wealth of information beyond Subsection (h).

We anticipate discussing the Subsection (i) restrictions, also known as the Technology Transition, in early 2024.

This will cover the constraints on specific Hydrofluorocarbons under the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act of 2020. Additionally, our Part 2 series addressed crossover provisions and commitments between Subsections (h) and (i).

Last week’s focus centered on the remaining elements of the ‘Proposed Rule – Phasedown of Hydrofluorocarbons’ segment under the AIM Act’s Subsection (h).

Topics included the new management deadlines for cylinders, the impending restriction on virgin refrigerant usage in 2028, and preparation for future reclamation refrigeration needs, along with expanded labeling and tagging protocols throughout the refrigerant lifecycle.

These regulations are extensive and multifaceted. To fully grasp the EPA’s rationale, expectations, and proposed directives, it’s essential to consider a wealth of information beyond Subsection (h).

This comprehensive perspective has informed our development of digital solutions to foster improved outcomes.

External resources include NFPA 2001, NFPA 2010, HEEP, HARC, the Halons Technical Options Committee (HTOC), its successor, the UNEP Fire Suppression Technical Options Committee (FSTOC), and many resources developed by all these various groups responsible for creating private environmental governance.

The fire suppression industry has a longstanding tradition of rallying around innovative solutions, particularly in response to environmental concerns.

This tradition is exemplified by the recent developments under the American Innovation and Manufacturing (AIM) Act, which aims to phase down hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) used in fire suppressant systems.

The AIM Act represents a pivotal step in U.S. environmental policy. It aims to significantly reduce the production and use of HFCs due to their high Global Warming Potential (GWP).

The schedule begins in January 2022 and aims for an 85% reduction by 2036.

📌 This comprehensive perspective has guided our development of digital solutions to promote improved outcomes.

History

The adoption of the Montreal Protocol in 1987 marked a crucial turning point in the fire suppression industry, necessitating a shift away from ozone-depleting substances, particularly halons. By 1994, developed countries had largely stopped producing and consuming key halons such as halon 1301 and halon 1211.

This regulatory shift prompted the creation and use of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) as effective alternatives for fire suppression. Although they are successful in putting out fires, HFCs are considered fluorinated greenhouse gases and add to greenhouse gas emissions when they escape into the atmosphere.

Over the past two decades, in line with the evolving standards established by the Paris Agreement and other environmental protocols, the fire suppression sector has continued to innovate. The industry’s response to the phaseout of ozone-depleting substances has been to adopt HFCs and inert gases like nitrogen and argon, codified in standards such as NFPA 2001.

This standard includes a variety of “halon alternatives,” such as HFC227ea (FM-200™, FE-227™), HFC-125 (FE-25™), HFC-23 (FE-13™), and FK-5-1-12 (Novec 1230™), as well as blends of various chemical agents.

However, it’s crucial to note that HFCs have a significant impact in terms of carbon dioxide equivalents, contributing to global warming by accumulating greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

This realization led to amendments in the Montreal Protocol, initiating a phasedown of HFC production and consumption starting in 2019, under certain conditions, to align emissions with global climate change mitigation efforts.

The fire protection industry has undergone significant transformation over the past three decades since the Montreal Protocol was introduced, striving for sustainable and efficient fire suppressant solutions.

This continuous evolution highlights a broader dedication to environmental responsibility, balancing effective fire suppression with the urgent need to curb greenhouse gas emissions and safeguard the ozone layer.

🧑🏻💻 Register Now for Our Free Webinar

Don’t let outdated budgeting models put your operations at risk. Join industry experts as we break down how current and future HVAC/R regulations can drastically impact your capital planning.

Fire suppressants like FM-200 (HFC-227ea) and HFC-125 have protected sensitive environments such as:

- Data processing centers

- Electronic areas

- Power generation facilities

- Hospitals

- Marine engine rooms,

- Museums

- Art galleries and rare booksellers

- Bank vaults

- Military Facilities & Aviation of all kinds

- Oil & Gas Exploration and Refineries

These settings necessitate the use of non-conductive, safe, and clean agents to avoid damage during fire suppression operations.

However, the environmental impact of these agents, particularly their Global Warming Potential (GWP), which can be thousands of times greater than that of carbon dioxide, has driven the search for more sustainable alternatives.

Regulations are driving change

In response to the directives of the AIM Act, the fire suppression industry is evolving by exploring new technologies, existing equipment, and substances that meet safety standards while aligning with environmental objectives.

Promising alternatives, such as 3M™ Novec™ 1230 Fire Protection Fluid, which boasts a significantly lower GWP compared to traditional HFCs, are already being adopted within the industry.

Alongside these global policy and industry shifts, advisory committees like the Halons Technical Options Committee (HTOC) have played a crucial role in addressing global warming.

Established after the Montreal Protocol in the late 1980s, the HTOC initially focused on finding replacements for ozone-depleting halons. As environmental regulations expanded to tackle climate change, the committee’s scope widened to include alternatives for HCFCs and HFCs, reflecting broader concerns about ozone depletion and global warming.

In recognition of this expanded role, the HTOC was renamed the Fire Suppression Technical Options Committee (FSTOC) in November 2022, as determined by the parties to the Montreal Protocol. The FSTOC now takes a comprehensive approach to evaluating fire suppressants, considering their effectiveness, safety, and environmental impact.

The AIM Act accelerates the timeline and intensifies the need to develop new rules and more stringent regulations to ensure that 1) the industry has access to sufficient materials to meet future fire suppression needs, and 2) fire suppressants are not inadvertently released into the environment.

🧑🚒 The fire suppression landscape is shifting fast — driven by regulation and environmental urgency.

Contact us to explore compliant, future-ready solutions tailored to your needs.

Background of HFCs in Fire Suppression

Hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, were initially developed as replacements for ozone-depleting substances like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halons.

They played a significant role in accelerating the phaseout of halon production, under the Montreal Protocol, an international treaty aimed at reducing the use of greenhouse gases to protect the ozone layer.

However, it was later discovered that HFCs are potent greenhouse gases with a long-lasting presence in the atmosphere.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has identified HFCs as major contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions. In response to this issue, the Montreal Protocol was amended in 2016 to initiate a reduction in HFC production starting in 2019.

Notably, a significant portion, ranging from 15% to over 60%, of HFC greenhouse gas emissions is attributed to their use in fire protection, as well as in air conditioning and heat pump equipment, and heating systems.

The U.S. fire protection industry has been at the forefront of addressing this issue.

Since 1989, it has been committed to reducing HFC and PFC emissions while ensuring safety from fire hazards, following the formation of a consortium named HARC by a group of industry stakeholders.

HARC is an important industry ally and resource

The Halon Alternative Research Corporation (HARC) is a non-profit organization that promotes the development and approval of environmentally acceptable halon alternatives.

HARC acts as an environmental protection agency, an information clearinghouse, and a central hub for collaboration between government and industry on issues critical to special hazard fire protection.

For more than three decades, HARC has been at the forefront of industry stewardship:

Information Clearinghouse and Collaboration Hub

The are central points for sharing information and fostering cooperation in the particular hazard fire protection community.

Industry Code of Practice

In coordination with various stakeholders, HARC developed an Industry Code of Practice to optimize the use of recycled halon.

Voluntary Code of Practice (VCOP)

Working alongside EPA, FEMA, FSSA, and NAFED, HARC contributed to creating the VCOP, which aims to reduce emissions from HFC and PFC fire protection agents.

Recycling Code of Practice (RCOP)

HARC established the RCOP to set standards for the safe and efficient recovery and recycling of halogenated clean agents, focusing on preventing contamination and minimizing emissions.

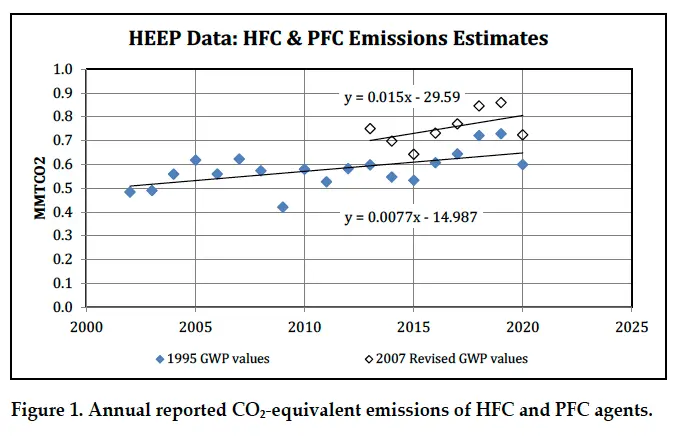

HFC Emissions Estimating Program (HEEP)

HARC developed HEEP to estimate HFC and PFC emissions from fire protection systems and assess the VCOP’s effectiveness.

The proposed rule by the EPA seeks to address gaps in current best practices identified by HARC for managing HFCs in fire suppression systems.

The objective is to improve reclamation and minimize emissions.

The new regulations will oversee the servicing, repair, disposal, and installation of equipment utilizing HFCs or their substitutes.

Additionally, the proposal emphasizes the distribution of HFCs, particularly the process of transferring them from larger to smaller containers within the supply chain.

Gaps remain, and they have an Impact on Operations

The primary aim of subsection (h) is to secure a future supply of recovered, recycled, or reclaimed refrigerant to meet upcoming demands. The EPA recognizes the significance of this goal.

A report from the Fire Suppression Technical Options Committee (FSTOC) sheds light on the stockpiles, emissions, and future needs of the entire fire suppression industry.

It highlights the prolonged use of fire-suppressant chemicals, which can remain in systems for decades, rarely leaking and only utilized during fire incidents.

For instance, some systems, like those in the filling facility of Valdez, Alaska, still contain over 100,000 pounds of Halons—a chemical phased out in 1994. Despite this, tens of thousands of Halon systems are still operational, gradually being replaced by HFC systems such as R-227, R-236, RT-23, and R-125.

The FSTOC finds it challenging to model emissions for these HFC systems due to their extensive use.

In the current global landscape of banking fire suppression agents, there is a significant gap in comprehensive knowledge regarding the management and banking of HCFCs and HFCs, despite their usage spanning over two decades.

As HCFCs are phased out and HFCs are gradually reduced, the importance of recycling and banking these substances is increasing.

Companies and government agencies face challenges with accuracy and accountability, and the scale and scope of these materials have been loosely managed, making it difficult for the EPA and other agencies to fully comprehend their total potential impact.

HFC recycling is widely practiced in the US, yet fire suppression companies do not report to the EPA.

📌 75% of HFCs used in servicing U.S. fire protection equipment are sourced from recycling, not new production.

While HCFC recovery from fire extinguishers does happen, reclamation processes are hindered by restrictions due to the proprietary compositions of the agents and complex blends.

The US Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) oversees recycling HFCs for military applications. Still, due to their widespread availability, there hasn’t been a need for a dedicated supply of HFCs for military purposes.

However, with the introduction of HFC phase-down regulations in 2022, there is likely to be a reassessment of the need for a dedicated military supply of HFCs.

Unresolved Issues

The EPA heavily relies on HARC’s insights and recommendations to craft solutions that align with the AIM Act’s goals.

Despite HARC’s efforts, there remain differences in HFC management practices.

Issue 1: Recycling Standard

HARC has voluntarily adopted the AHRI 2016 standard, the same as that used in the refrigerant HVAC/R services industry.

Yet, there is no obligatory requirement or penalty for failing to meet this standard. Furthermore, the EPA permits this material to enter the supply chain for service and maintenance without quality assurance.

Issue 2: Disclosure

Neither members nor stakeholders report their activities to AHRI or disclose them to the EPA. Currently, EPA-certified reclaim companies must report their annual recycling activities. Many fire suppression systems containing HFCs also have blends of other components, making them impure and harder to recycle.

Due to this complexity, the industry acknowledges the challenges but needs to clarify the fate of non-recyclable materials. My research found no documented waste sent to destruction facilities. I used carbon offset markets as a reference; none were noted over the past five years. EPA is therefore proposing:

- Reporting the quantity of material by regulated substance, defined by sold, recovered, recycled, and virgin, related to servicing and installation.

- Detailing the total mass of each regulated substance, broken down by sold, recovered, recycled, and virgin.

- Providing information on the total mass of waste products sent for disposal and details about the disposal facility if the reporting entity does not process waste.

Issue 3: Definitions for what is recyclable.

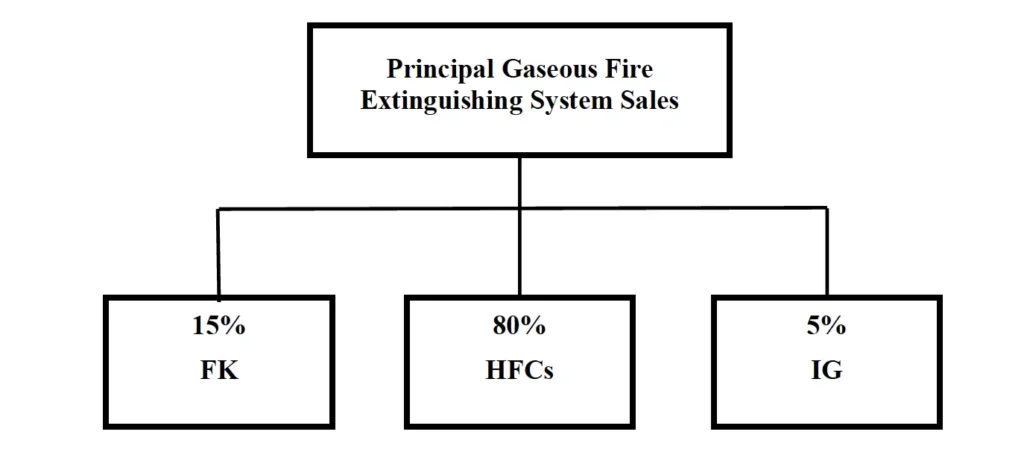

Despite the relatively small proportion of HFCs used in fire suppression compared to other applications, any global phase-down could impact the fire suppression sector. As new HFC production decreases due to phase-down regulations, recycling becomes increasingly vital as an alternative source.

Historically, the recycling and reuse of HFCs in fire protection equipment have been common practices. However, as highlighted by the FSTOC, the diverse applications of HFCs and the intricate nature of patented blends containing these chemicals present significant challenges for recycling and processing, thereby limiting the overall effectiveness of recycling efforts.

Expected outcome: EPA has proposed that the Fire Suppressants sector report to the EPA annually.

Issue 4: QR Codes or Labeling

The requirement for machine-readable tracking identifiers, like QR codes, on all HFC containers applies to fire suppression systems/cylinders.

The EPA’s proposal includes these identifiers on containers containing HFCs used in servicing, repairing, or installing fire suppression and refrigerant-containing equipment.

This is part of the EPA’s broader effort to ensure the proper management and tracking of HFCs; however, the staggered compliance dates would allow different entities involved in the supply chain to adjust to and comply with the new requirements.

The requirement or specifics of dates should be included in Subsection (h) dates.

EPA proposes tracking disposable cylinders to reclaimers or fire suppressant recyclers, which will be required as of January 1, 2026. This date aligns with the proposed requirement for reclaimers and fire suppressant recyclers to track containers they fill, sell, distribute, or offer for sale or distribution with regulated substances that could be used in the servicing, repair, or installation of certain types* of refrigerant-containing equipment or fire suppression equipment.

Maintenance and Handling Requirements

The EPA heavily depends on organizations such as TEAP, FSTOC, HARC, HEEP, NFAP 2001, and NFPA 2010 to structure their control strategies concerning HFCs in the fire suppression sector.

The TEAP’s FSTOC has observed that the U.S. phasedown of HFCs profoundly affects the production, consumption, and pricing of HFC fire extinguishers.

The factors contributing to this include the high Global Warming Potential (GWP) of HFCs, the GWP-weighted allocation mechanism in the U.S., global warming concerns, and market dynamics that determine which HFCs are produced or imported based on their GWP and anticipated market requirements.

🧑🏻💻 Register Now for Our Free Webinar

Don’t let outdated budgeting models put your operations at risk. Join industry experts as we break down how current and future HVAC/R regulations can drastically impact your capital planning.

List of Proposed Requirements

- Prohibition on releases due to the owner’s failure to maintain the system properly.

- New Training for Fire Suppression Technicians January 1, 2025 (Page 172)

- EPA proposes new disposal guidelines for HFCs from fire suppression systems.

- Options for disposal include:

- Recycling through certified fire suppressant recyclers or reclaimers.

- Destruction using EPA-approved controlled processes.

- Current standards (NFPA 2001 for systems, NFPA 10 for extinguishers) lack specific HFC disposal requirements for existing equipment, so they have proposed adding this requirement.

- EPA seeks public feedback on using recycled HFCs for servicing/repairing fire suppression equipment.

- Types of fire suppression equipment should use recycled HFCs for servicing/repairs.

- Should we mandate using only recycled HFCs for these purposes?

- Possibility of gradually introducing the use of recycled HFCs.

- Practices to reduce HFC emissions during recycling for servicing/repairs.

- Whether entities should adhere to industry standards like NFPA 2001, NFPA 10, and various ASTM specifications.

- Feedback is requested on a proposed compliance date of January 1, 2025, for using recycled HFCs, with alternative dates of January 1, 2026, or January 1, 2027, also being considered.

- Owners and operators dispose of HFCs used as fire suppression agents by sending them for recycling to a fire suppressant recycler or a reclaimer certified under 40 CFR 82.164 or arranging for its destruction using one of the controlled processes listed in 40 CFR 84.29.

- Record-keeping

- EPA proposes annual reporting requirements for entities handling regulated substances, including details on quantities sold, recovered, recycled, and virgin HFCs.

- Record-keeping requirements may overlap with those under 40 CFR part 84, subpart A; EPA seeks comments on this potential overlap and the timing of these requirements.

- Covered entities should keep fire suppression technician training records, which the EPA may review as needed.

- Facilities must document that they have provided appropriate training to personnel.

- Records confirming HFC recovery from equipment slated for disposal should be kept for three years.

- Data Collection and Reporting

- Efforts to identify reporting parties and collect relevant data.

- Adjustments and refinements in the data collection process over time.

- Inclusion of direct recycling data in the reporting framework.

- Results and Analysis

- Annual reporting of emissions data and calculation of CO2 equivalent emissions.

- Observations on year-to-year variations in greenhouse gases and trends in emissions.

- Possible explanations for climate change: the stability of carbon dioxide or changes in carbon dioxide emission rates.

- January 1, 2025, all initial charges of fire suppression equipment should be used by recycled HFCs, thanks to extending this compliance deadline to 2026 or 2027. (with some exceptions for critical applications)

The EPA recognizes the intricate process of approving fire suppressants for specialized uses, which often require thorough testing by organizations such as the FAA, USCG, and DoD. To address this, the EPA suggests allowing limited HFC releases under certain conditions:

These exemptions apply when alternative agents are not viable options, and the failure of existing equipment could pose significant risks to human safety or the environment.

📌 These exemptions are strictly for testing purposes, essential for demonstrating functionality, and do not cover the emergency use of HFCs for actual fire suppression.

Looking Forward: Adapting Fire Suppression Management to Align with EPA Sustainability Standards

To comply with the EPA’s updated regulations and to foster sustainability, businesses need to enhance their management of fire suppression and air conditioning systems. The following points highlight the necessary updates for servicing existing air conditioning systems, equipment, and best practices:

Sustainable Purchasing Practices

Update purchasing protocols to reflect new fire suppression standards, incorporate staff training, amend supplier agreements with compliance clauses, and favor eco-friendly equipment options.

Digital Inventory Management

Establish a digital twin for comprehensive tracking of fire suppression assets, cataloging every HFC-containing component from inception to retirement.

Record-Keeping and Reporting

Implement an extensive record-keeping system to log all HFC-related operations, focusing on environmental impact and regulatory compliance.

DOT Regulation Adherence

Develop clear protocols for handling cylinders as they approach or surpass their DOT expiration, following EPA’s safety and environmental care guidelines.

Advanced Training and Awareness

Initiate thorough training programs for technicians that address new regulations, safe handling, and preventive maintenance to avert accidental HFC discharges.

Conclusion

The fire suppression industry has historically depended on self-regulation and private environmental governance, with organizations like TEAP, FSTOC, and HARC spearheading initiatives without formal accountability.

As the EPA intensifies its efforts to manage the environmental impact of HFCs in this sector, there is a pressing need for more precise and comprehensive regulations that align with existing HVAC/R system standards.

The EPA’s proposed measures to reduce emissions, set to begin in January 2025, include mandatory system maintenance, specialized technician training, and specific guidelines for HFC disposal, such as recycling and controlled destruction.

These initiatives address the high global warming potential of HFCs and the market dynamics that influence their production and use.

By integrating public feedback and industry standards into its rulemaking, the EPA aims to ensure that stakeholders in the fire suppression industry adhere to clear, enforceable standards that address both environmental concerns and industry requirements.

Comments on this notice of proposed rulemaking were all submitted by December 18, 2023. For the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), comments on the information collection provisions are best considered if received earlier.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) hosted a virtual public hearing on November 3, 2023, where they discussed these issues, accepted questions, and gathered additional comments.

A further meeting is scheduled during a GreenChill discussion several weeks prior.

Details about the virtual public hearing, including the date, time, and other relevant information, can be found on the EPA Website: Protecting Our Climate by Reducing Use of HFCs.

Outstanding Issues Needing Clarification: Impact of EPA’s RCRA Rules on Supply Chain

Identification of Flammable Refrigerants in RCRA Chemical List

- Is there a specific listing of flammable refrigerants under the RCRA chemical list?

- If not, are there any plans to update the RCRA list to include these?

RCRA Listings for EPA Reclaim Companies:

- Are there specific listings for US EPA reclaim companies in the RCRA database?

- What are the expected registration requirements for these companies following the implementation of the new rule?

- How are reclaimers expected to manage their RCRA solid waste obligations, and what are the reporting and audit processes?

Supply Chain Responsibilities for Distributors and Aggregators:

- Does the EPA specify a weight threshold or limit under RCRA that triggers responsibility for distributors and aggregators handling recovery cylinders?

Regulatory Stance on Venting of Ignitable Refrigerants:

- Does the EPA’s position on venting versus recovery of ignitable refrigerants imply a tacit acceptance of venting these substances?

- What are the legal implications for technicians venting ignitable substances in the commercial sector?

- Is there a corresponding requirement from OSHA or NIOSH regarding the responsibility to recover these substances?

Regulatory Updates Specific to RCRA or Incorporated in Subsection H:

- Are the changes to RCRA related to the phasedown of hydrofluorocarbons part of a separate regulatory update, or are they included in Subsection H as outlined in the proposed rule available in the Federal Register Document?

📌 Clear guidance is essential for industry-wide compliance and sustainability.

Connect with us to stay ahead of evolving RCRA regulations and ensure your team is prepared.

The outstanding issues related to the EPA’s Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) rules highlight an essential phase in the ongoing effort to enhance environmental management and safety.

While there are areas needing further clarification, such as the identification of flammable refrigerants in the RCRA chemical list and the specific responsibilities of distributors, aggregators, and reclaim companies, it is encouraging to see the proactive steps taken by the EPA toward environmental conservation and public health protection.

The engagement in these complex matters, including the nuanced approach to venting versus recovery of ignitable refrigerants, demonstrates a commitment to environmental stewardship and responsible regulatory oversight.

The potential integration of RCRA changes with other regulatory frameworks, such as those from OSHA or NIOSH, further exemplifies a comprehensive approach to environmental management.

We commend the efforts made by the EPA and encourage ongoing communication and transparency. Providing clear guidelines and regulatory updates, particularly concerning the changes proposed under Subsection H, will be crucial in supporting stakeholders throughout the supply chain.

This clarity will enable them to adapt effectively and comply with the regulations, ultimately contributing to the larger goal of sustainable environmental practices.

As progress continues, we look forward to further advancements and detailed guidance from the EPA.

Collaborative efforts are key to ensuring that all involved parties are well-informed and equipped to meet both current and future environmental challenges with confidence and commitment.