Practical Guide for Buyers and Sellers of Refrigerant-Based Carbon Offsets

Pearse & Böhm warned that offsets lacked teeth. Refrigerants answer that warning: forcing the buyer’s test, shifting the seller’s burden, and making proof of the true currency of climate finance.

Table of Contents

ToggleA 10-Year Check-In on Carbon Market Predictions

In 2015, Rebecca Pearse and Steffen Böhm published a sharp critique of carbon markets:

Ten Reasons Why Carbon Markets Will Not Bring About Radical Emissions Reduction.

Their argument was not just academic; it was a structural warning. They claimed that weak regulation, fraud, displacement of real mitigation, inequity, and overreliance on market logic would doom carbon markets to irrelevance or worse: they would distract from the real work of phasing out fossil fuels.

At the time, carbon markets were still in their early stages of development.

The European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) was recovering from its early surplus problems, the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) had already collapsed, and voluntary markets were still small.

Ten years later, the global picture is mixed. Carbon markets have expanded dramatically:

- Compliance schemes now regulate billions of tons of CO₂e across Europe, China, California, and elsewhere.

- Voluntary carbon markets have grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry, adopted by corporations as part of their “net-zero” strategies.

- Refrigerant destruction markets have emerged as a unique high-integrity niche, providing measurable and permanent emissions reductions. In most developed countries, the reliance on artificial refrigeration and mechanical refrigeration has made refrigerant management a key part of emissions reduction strategies.

In developed countries, advances in refrigeration technology have transformed food distribution and urban settlement patterns, enabling large cities to thrive and changing the way agricultural production supports urban populations.

These advances were made possible by the work of American inventors and American physicians, such as John Gorrie, who played a significant role in the development of refrigeration technology.

As carbon markets have evolved, new technology such as digital MRV (monitoring, reporting, and verification) and advanced refrigeration systems has enabled more accurate tracking and production of carbon offsets.

Yet the weaknesses identified in 2015 remain highly visible. Investigations have exposed “phantom credits,” baseline manipulation, and widespread double accounting. Markets have bent the curve (emissions reductions of 5–15% have been documented), but rarely have they shifted the system.

🚨 Carbon markets expanded, tech evolved, yet loopholes thrive. Inspect, question, act today.

The widespread adoption of domestic refrigerators has contributed to increased emissions of greenhouse gases, making the management of refrigerants and the reduction of their environmental impact even more critical.

Refrigerants are also widely used in air conditioners and automotive air conditioning, where their environmental impact and sustainable management are important considerations. Achieving and maintaining lower temperature environments is essential for food preservation and urban living.

Today, I am revisiting Pearse & Böhm’s ten criticisms, weighing them against the evidence, integrating lessons from the rise and collapse of CCX, and highlighting counterexamples, such as ReCoolit’s refrigerant destruction program.

My goal is to provide buyers, project managers, sellers, and generators (particularly those in the refrigerant industry) with a practical, evidence-based guide to avoid the pitfalls of the past decade.

Selecting the right refrigerant project/partner is a crucial consideration for both buyers and sellers, particularly as the industry transitions to more environmentally friendly options.

Historically, other gases such as ammonia and sulfur dioxide were used before the adoption of modern refrigerants. Buyers and sellers can sell offsets to support climate goals and help secure environmental benefits for future generations.

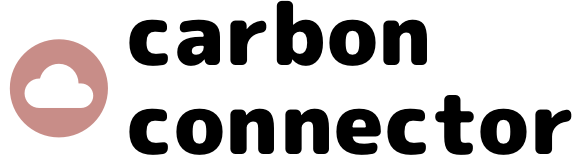

Commonly Used Refrigerants: What Buyers and Sellers Need to Know

Refrigerants are the lifeblood of commercial refrigeration, air conditioning systems, and a wide array of cooling technologies that keep our environments comfortable and our food supplies safe.

As demand for efficient cooling continues to grow in both commercial and industrial applications, understanding the landscape of commonly used refrigerants is essential for anyone involved in buying or selling carbon offsets related to these systems.

HFC Global Warming Potential (GWP100) Values in AR4, AR5, and AR6

| Designation | Formula | F-Gas Regulation AR4 | AR5 | AR6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFC-23 | CHF₃ | 14800 | 12400 | 14600 |

| HFC-32 | CH₂F₂ | 675 | 677 | 771 |

| HFC-125 | CHF₂CF₃ | 3500 | 3170 | 3740 |

| HFC-134a | CH₂FCF₃ | 1430 | 1300 | 1530 |

| HFC-143a | CH₃CF₃ | 4470 | 4800 | 5810 |

| HFC-152a | CH₃CHF₂ | 124 | 138 | 164 |

| HFC-227ea | CF₃CHFCF₃ | 3220 | 3350 | 3600 |

| HFC-236fa | CF₃CH₂CF₃ | 9810 | 8060 | 8690 |

| HFC-245fa | CHF₂CH₂CF₃ | 1030 | 858 | 962 |

| HFC-365mfc | CF₃CH₂CF₂CH₃ | 794 | 804 | 914 |

Commercial Use of Carbon Offsets

In the commercial and industrial sectors, carbon offsets have become a widely used strategy for managing greenhouse gas emissions.

Businesses across various industries, from supermarkets with extensive commercial refrigeration units to office buildings with large-scale air conditioning systems, are turning to carbon offsets to offset the emissions generated by their operations.

By purchasing carbon offsets, companies can compensate for the environmental impact of their air conditioning systems, refrigeration systems, and other cooling technologies, helping them achieve carbon neutrality and meet sustainability targets.

The HVAC industry, in particular, has embraced carbon offsets as a practical solution for reducing the carbon footprint of both new and existing systems.

For example, a company operating a fleet of commercial refrigeration units can invest in carbon offsets to counterbalance the emissions produced by these systems.

This approach not only demonstrates environmental responsibility but also aligns with growing regulatory and consumer expectations for sustainable business practices.

As a result, the commercial use of carbon offsets has become an integral part of emissions management strategies in many countries, supporting the broader goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions across commercial and industrial sectors.

🚨 Industrial cooling drives efficiency but emits GHGs. Upgrade systems, offset impact, lead change.

Industrial Applications

Refrigeration plays a vital role in a wide range of industrial applications, from preserving food in commercial refrigeration facilities to cooling machinery and products in manufacturing plants.

In these settings, refrigerants play a crucial role in absorbing heat and maintaining lower temperatures, thereby ensuring the safe and efficient operation of equipment and the quality of temperature-sensitive goods.

The most commonly used refrigerants in industrial applications today are hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), which offer lower ozone depletion and global warming potential compared to older substances.

Despite these improvements, the use of refrigerants in industrial applications still contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, making it increasingly necessary to adopt energy-efficient refrigeration systems and offset remaining emissions through carbon offsets.

The industry is also exploring new technologies, such as magnetic and elastocaloric refrigeration, which promise more environmentally friendly and energy-efficient cooling solutions.

By combining advanced refrigeration systems with the purchase of carbon offsets, companies can minimize their environmental impact, reduce energy consumption, and support the transition to a more sustainable industrial sector.

Understanding Carbon Credits

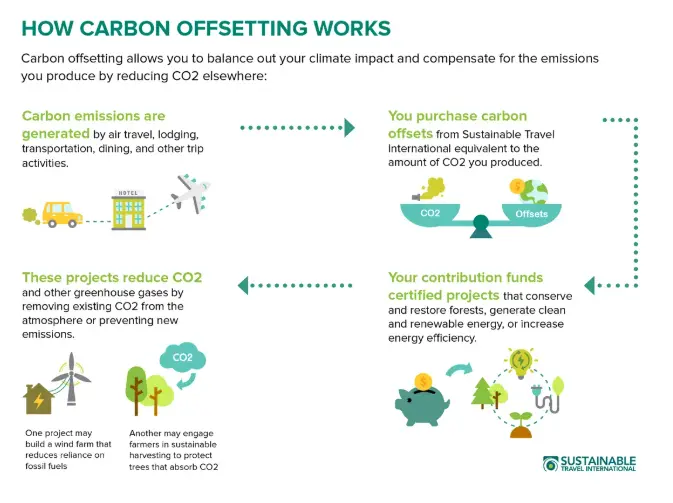

Carbon credits are tradeable certificates that represent the removal or reduction of one ton of carbon dioxide or its equivalent in greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere.

These credits are awarded to projects that can demonstrate a verifiable decrease in emissions, such as the installation of energy-efficient refrigeration systems, the adoption of environmentally friendly refrigerants, or the implementation of advanced energy-saving technologies.

The concept of carbon credits has roots in the early twentieth century, but it was the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 that truly propelled their use as a market-based tool for emissions reduction.

Today, carbon credits are a cornerstone of efforts to manage energy consumption and reduce the carbon footprint of refrigeration systems worldwide.

By investing in projects that lower emissions (whether through improved efficiency, innovative refrigerants, or renewable energy) companies and individuals can purchase carbon credits to offset their own greenhouse gas emissions.

This not only helps achieve compliance with regulatory requirements but also supports the transition to a low-carbon economy.

In the context of refrigeration, earning carbon credits often involves upgrading to systems that use less energy and more sustainable refrigerants, directly contributing to global emissions reduction goals.

Revisiting the Ten Criticisms: A Decade in Review

Pearse & Böhm’s ten criticisms are evaluated below with the benefit of a decade of hindsight.

1. Ineffectiveness in Reducing Emissions

Evidence: A 2024 meta-analysis of 80 ex-post studies across 21 pricing schemes showed statistically significant reductions of –5% to –21%, with corrected estimates of –4% to –15%.

The EU ETS resulted in ~10% reductions between 2005 and 2012, with no significant impact on profits or jobs.

The average price of carbon offsets has played a key role in influencing market participation and investment, as higher prices can incentivize more robust emissions reductions.

Verdict: Partially refuted. Impact is real, but scale is insufficient for 1.5 °C.

2. Weak Regulation & Enforcement

Compliance markets (EU ETS, China) have improved penalties and verification. But voluntary markets remain lightly policed — registries track transactions, not credit quality.

Verdict: Still true. Robust enforcement is rare.

3. Fraud and Manipulation. Aggregate Sourcing Without Disclosure

Credits are generated from refrigerants collected at many individual sites (supermarkets, cold storage warehouses, building decommissions, etc.).

Registries (ACR, Verra, Gold Standard) require proof of destruction and chain-of-custody, but they do not require public disclosure of every source site.

The Double-Claim Risk

- Each of those source sites could still report in their ESG filings that they reduced their refrigerant inventory (because they shipped out and destroyed the gas).

- Meanwhile, the project developer generates offsets for the same destruction event, which are then sold to a buyer who retires them.

- Result: The same ton of CO₂-equivalent reduction is potentially being claimed three times: once by the facility, once by the developer, and once by the buyer.

Why This Mirrors Pearse & Böhm’s Concerns

- This is a textbook case of the structural weakness they highlighted: commodification without strict accounting rules.

- Just like the CCX allowed protocols that prioritized transaction volume over rigor, refrigerant destruction credits today risk being undermined if the exclusivity of claims is not enforced.

4. Legitimacy Crisis

Public trust in voluntary credits has suffered repeated blows. Compliance schemes retain more credibility, but only with strict rules.

Verdict: Confirmed. Legitimacy is fragile.

5. Offsets Displace Rather Than Reduce

Most firms still buy offsets as a substitute for internal reductions. Studies show that only ~12% of voluntary credits correspond to real decreases.

Verdict: Confirmed. Displacement remains common.

6. Policy Distortion

Markets have delayed stronger rules, especially when industries lobbied for free allocations.

Verdict: Confirmed. Lock-in remains a risk.

7. Delay in Fossil Fuel Phase-Out.

Carbon prices alone have not driven a complete phase-out; complementary policies remain necessary. In the refrigerant space, carbon offsets are not driving change; regulations are.

Verdict: Confirmed.

8. Equity Concerns

Some revenue recycling exists, but benefits remain uneven.

Verdict: Partially addressed.

9. Complexity and Opacity.

Digital MRV has improved transparency, but small actors still find markets inaccessible. The importance of low-cost solutions is critical for widespread adoption, as affordable offsets and technologies can help more participants engage in carbon markets.

Verdict: Partially addressed.

10. Overreliance on Commodification.

The framing of carbon as a commodity still dominates. However, some market outcomes have demonstrated positive impacts on the environment, such as improved air quality and ecosystem restoration.

Verdict: Still true.

Of all credit types, refrigerant destruction projects are often held up as a gold standard. They are event-based, measurable, and permanent. When CFCs or HCFCs are incinerated in a high-temperature plasma arc with 99.9999% destruction efficiency, the reduction is indisputable.

And yet, even here, pitfalls remain. The problem lies not in the destruction, but in the sourcing. Destruction projects typically aggregate gases from dozens or hundreds of facilities: grocery chains, cold storage warehouses, decommissioned industrial systems. These facilities may — and often do — report the reduction of their refrigerant inventory in their own ESG disclosures.

If the project developer then claims credits for destruction, and a third-party buyer retires those credits, the same reduction has been claimed three times.

Summary Alignment: Rights & Risks in Refrigerant Offsets

| Topic | Rule / Guideline | Relevance to Refrigerants |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusive Claim Ownership | GHGP requires unambiguous ownership; only purchaser can claim | Generators must not claim sold refrigerant creditsPhoenix Strategy Group +2, Lune, KPMG |

| Registry-Based Retirement | Credits must be retired with serial IDs to prevent double use | Ensures one claim per tonKPMG |

| Buyer Reporting Requires Credit Ownership | Only claim retired credits in your name | Users of refrigerant credits must hold proof before inclusionavrn.co, persefoni.com |

This isn’t hypothetical. A-Gas, Rapid Recovery, and similar operators collect refrigerants through on-site recovery, cylinder swaps, or distributor reclaim programs.

The destruction event is real and verified, but the facility-level reporting is opaque. ESG reporters may still book reductions while credits are simultaneously issued and sold.

Registries like ACR require chain-of-custody documentation, but they do not require public disclosure of every source site or explicit attestations that the originating company has not claimed the reduction elsewhere. That gap leaves room for double-counting; precisely the kind of “commodification without accountability” Pearse & Böhm warned against.

Evidence of Impact: Bends, Shifts, and Stalls

If the previous section revisited the claims of 2015, this section asks: what actually happened?

Bends

Most compliance markets (EU ETS, RGGI, China pilots) bent the curve; emissions fell faster in covered sectors than in uncovered ones.

But when economic growth rebounded, emissions rose again. The production of verified emissions reductions in these markets contributed to lowering greenhouse gases, demonstrating the importance of robust measurement and verification.

Shifts

Rare. Shifts occurred only when markets were paired with:

- Phase-out mandates (e.g., banning coal or HFCs).

- Rising price floors.

- Complementary policies like renewable subsidies.

- Exclusive claim rules (to prevent double accounting).

In sectors such as food and industry, the impact of refrigeration is significant; cooled environments and maintaining low temperatures are essential for reducing emissions, as they help preserve goods and improve energy efficiency.

Refrigeration systems are designed to maintain cool environments, which are crucial for both preserving perishable goods and enhancing overall energy efficiency.

📌 Lesson: Markets can bend. They shift only when integrated into policy and governance, highlighting the cycle of policy implementation and market response.

Quality, Integrity, and the Market’s Fragile Core

Carbon markets thrive or falter on trust. Without integrity, credits are worthless.

The Quality Gap

High-integrity, event-based credits (like refrigerant destruction) contrast sharply with modeled, avoidance-based credits. The destruction of refrigerants that do not meet the criteria of an ideal refrigerant is prioritized to ensure only the most effective and environmentally responsible substances are used.

Investigations confirmed systemic overestimation: rainforest offsets, soil carbon protocols, and “phantom” credits.

The Role of Event-Based Credits

The destruction of refrigerants, a permanent, measurable, and irreversible process, provides proof that markets can deliver high-quality credits if designed correctly.

In the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle, the refrigerant first passes through the condenser, where it is cooled and condensed into a liquid.

This liquid refrigerant then moves to the evaporator, where it absorbs heat from the surroundings and evaporates, producing the cooling effect essential for refrigeration.

Evaporators play a crucial role in system efficiency by ensuring complete vaporization of the refrigerant and effective heat transfer.

The process of evaporation, which is key in both ancient and modern cooling methods, underlies the ability of refrigerants to achieve effective cooling.

During operation, a refrigerant absorbs heat as it evaporates, making it essential for cooling, but if released, it can harm the environment.

Destroying these refrigerants prevents further environmental harm, including the protection of the ozone layer from depletion.

Co-benefits include a positive impact on the environment through reduced emissions and improved sustainability.

Avoiding Pitfalls: Offsets vs. Insets

This section addresses the practical mechanics of credits — and how offsets differ from insets.

Offsets are reductions outside a company’s boundaries.

A generator reduces emissions, produces verified offsets, sells credits, and a buyer retires them. Entities can sell offsets as part of their emissions reduction strategy, often using market-based solutions such as forest preservation or land management projects.

The generator gets paid; the buyer gets the claim. New technology is improving verification processes for offset production, making monitoring and reporting more accurate and efficient.

These projects can also deliver climate and ecosystem benefits that support future generations.

Insets are reductions within a company’s own supply chain.

The company invests in reduction and keeps the claim. Insets are structurally less vulnerable to double accounting, since no external party is involved.

Like offsets, insets can provide long-term environmental benefits for future generations.

Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV): The Architecture of Trust

Integrity is not perfection. The most trustworthy systems detect failures and report them.

Case: A refrigerant leak reduction project promises a decade of savings.

By Year 7, leak rates exceed thresholds. Instead of hiding it, the MRV system documents the reversal. Fewer credits are issued; records are updated. The production of verified credits depends on accurate monitoring and transparent reporting, ensuring only legitimate emissions reductions are credited.

📌 Lesson: A reported “failure” is stronger proof of integrity than a perfect record based on assumptions.

MRV has matured:

- Level 1: Manual audits.

- Level 2: Digital spot checks.

- Level 3: Continuous, tamper-proof digital MRV enabled by new technology, which allows for more accurate and efficient verification.

The MRV process operates as a cycle of monitoring, reporting, and verification, ensuring ongoing integrity and accountability.

Policy Integration: Markets Can’t Stand Alone

Markets function most effectively when embedded in a policy framework. Without mandates, they drift.

CCX proved this point: when U.S. federal climate policy collapsed, demand disappeared.

Modern examples demonstrate the opposite: refrigerant destruction credits, aligned with the Kigali Amendment and F-gas regulations, create permanence.

Policy goals increasingly focus on protecting the environment. Policy targets now emphasize reducing greenhouse gases.

The impact of these policies is seen in the production of verified emissions reductions. Effective policy implementation requires attention to the entire policy cycle.

The Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX): Pioneer and Cautionary Tale

The CCX was the first voluntary, legally binding carbon market. It was visionary, but it collapsed by 2010.

Your firsthand experience adds critical detail:

Oversupply

At one point, 1.5 million offsets in a single protocol flooded the market, overwhelming the supply and outpacing the production of verified credits.

Weak protocols

Credits for projects with dubious climate value, even speculative ones.

Misaligned incentives

CCX earned fees on transactions, so volume > integrity.

Buyer distortion

Firms like Alcoa earned more from CCX credits than from aluminum, reshaping operations around arbitrage, not mitigation.

The availability of low-cost offsets encouraged participation but undermined market integrity.

Why it failed:

- No federal cap-and-trade to anchor demand.

- Weak protocols created mistrust.

- Prices collapsed to pennies, highlighting the importance of understanding the average price of offsets to ensure market stability and value.

📌 Lesson: Governance matters. Without rigor, carbon markets become financial shells. Market dynamics often follow a cycle of boom and bust, emphasizing the need for robust oversight.

ReCoolit: Integrity by Design

ReCoolit emerged from the failures of past markets, such as CCX.

Where others diluted integrity for growth, ReCoolit made integrity its competitive edge. Its model is uncompromising but straightforward: destroy high-GWP refrigerants that would otherwise be vented, and prove it.

Why does it work?

Event-based

Every credit is tied to a documented destruction event, rather than a projection or model.

Permanent

Once destroyed, refrigerants cannot return, locking in climate benefits for generations.

Exclusive

The buyer alone can claim the credit; the generator cannot double-count.

Transparent

A tamper-proof chain of custody ensures traceability from cylinder to destruction.

Source-visible

Unlike other markets that leave refrigerant origins a mystery, ReCoolit shows the full lineage. Buyers see what gas was destroyed, where it came from, and why it matters.

This visibility is the key. Without it, offsets are promises on paper. With it, they become verifiable proof.

The Impact

ReCoolit not only delivers climate gains but also cleans up local pollution, eliminating toxic refrigerants from leaking into the air and water.

In doing so, it ties global carbon markets to tangible environmental outcomes, proving that offsets can be more than a financial instrument; they can be an act of stewardship.

Market Signals and Price Stability

Markets need credible price signals. Volatility undermines investment.

CCX: collapsed prices destroyed confidence.

EU ETS: Market Stability Reserve restored confidence. ReCoolit and refrigerants: demand smoothing across jurisdictions protects value.

Looking ahead, new technology is expected to play a significant role in shaping the market, improving remote monitoring and verification processes for carbon sequestration and offset production.

As the market evolves, it follows a cycle of development, with periods of growth, correction, and stabilization. Future offset generation will increasingly focus on the production of verified credits, leveraging technological advancements to ensure accuracy and transparency.

Equity, Co-Benefits, and the Just Transition

Markets judged only on carbon miss the point; distribution matters.

High-integrity refrigerant programs create jobs, protect technicians, and prevent toxic venting, direct local co-benefits.

When buying or selling, prioritize projects that protect the environment and support long-term benefits for future generations.

This improves legitimacy, beyond carbon math.

Carbon Offset Registry

A carbon offset registry is a critical component of the carbon market infrastructure, providing a transparent and reliable system for tracking the issuance, ownership, and retirement of carbon offsets.

These registries ensure that each carbon offset represents a real, measurable, and additional reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, meaning the reduction would not have occurred without the offset project.

Leading registries, such as the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Gold Standard, are widely used to certify and track offsets from various projects, including those related to air conditioning systems, refrigeration systems, and other industrial processes.

By using a carbon offset registry, companies and individuals can confidently buy and sell carbon offsets, knowing that their transactions are recorded and verified in a secure system. This is especially important in the context of climate change, where the credibility of emissions reductions is paramount.

Registries help prevent double-counting and ensure that each offset is claimed only once, thereby supporting the integrity of the carbon market.

For buyers and sellers in the refrigeration and HVAC industries, participating in a reputable carbon offset registry is a crucial consideration for achieving genuine and lasting reductions in emissions.

The Decade Ahead: From Bend to Shift

Pearse & Böhm were half right. Markets bend, rarely shift. But BloombergNEF reminds us the next decade is decisive: the rules set today will determine whether carbon markets are trusted financial instruments or written off as failed experiments.

Diverging Pathways

BloombergNEF’s research shows just how different the futures could be:

Removal-Only Market

If credits are restricted to durable removals (like carbon mineralization or direct air capture), average prices could hit $127/ton by 2050, with spikes to $146/ton by 2030. A small, high-quality market, but very expensive.

Weak Voluntary Market

If integrity problems persist, demand collapses, leaving prices stuck around $13–14/ton into 2050. This outcome would confirm Pearse & Böhm’s warning that carbon markets enable “pollution rights” without impact.

High-Quality Voluntary Market

If integrity, transparency, and standardized rules are enforced, prices could rise sharply as net-zero deadlines approach, as high as $238/ton by 2050.

In this world, markets scale massively, financing billions of tons of real reductions.

What Drives the Outcome

Corporate Demand

Net-zero commitments remain the biggest demand driver, with companies projected to need billions of tons of credits.

Policy Shifts

China is expanding coverage by 2027 and building a voluntary market by 2030. The EU may allow imports of high-quality credits to hit its 2040 climate target. The U.S. remains politically uncertain, but methane rules and state-level policies will play a role.

Supply Challenges

Removal technologies like DAC are expensive and energy-intensive. Nature-based solutions face permanence risks. Scaling supply is as critical as ensuring demand.

Investor Mobilization

Wall Street banks and private equity are positioning carbon as a mainstream commodity, expecting growth if credibility is restored.

The Connection to Pearse & Böhm

Pearse & Böhm argued that weak rules and commodification would undermine ambition.

Bloomberg’s scenarios make that argument quantitative: weak integrity locks prices low and leaves markets irrelevant.

Strong rules push carbon toward parity with other traded commodities, making it a real driver of decarbonization.

The Lesson

The decade ahead is not abstract. It is binary:

- Weak rules → weak demand, low prices, markets dismissed.

- Strong rules → strong demand, high prices, markets mature into structural tools.

Integrity, transparency, and accounting are not academic debates — they are the difference between a $13 market and a $238 market.

🚨 The choice is clear: build trust today, or watch carbon markets fade tomorrow.

Leak Detection-as-a-Service (LDaaS): Closing the Verification Gap

If refrigerant destruction represents the end-of-life solution, leak detection is its preventive counterpart. While destruction credits eliminate high-GWP gases permanently, most of the climate damage from refrigerants occurs long before systems are decommissioned — through leaks in day-to-day operation.

These leaks can account for 20–30% of a system’s charge over its lifespan.

That is why leak detection, done as a service, is emerging as one of the most promising additions to carbon credit integrity.

Why Leak Detection Matters?

Pearse & Böhm warned about opacity and unverifiable claims in carbon markets. Leak detection directly addresses that weakness. By providing continuous, verifiable data on refrigerant loss, LDaaS transforms hidden emissions into observable, reportable events.

Without leak detection, offset projects rely on estimates of refrigerant leakage avoided through maintenance.

With LDaaS, those claims can be tied to real-world measurements: when a leak is found, quantified, and prevented, the avoided emissions can be verified with confidence.

The LDaaS Model

Leak detection-as-a-service functions much like MRV for refrigerant systems:

Sensors and IoT Platforms

Devices monitor refrigerant levels, pressure, and flow in real time.

Detection and Dispatch

Anomalies trigger technician response; leaks are identified and repaired.

Data-to-Credit Conversion

Verified reductions are calculated based on the amount of refrigerant saved from release.

Independent Verification

Third-party auditors confirm both the detection and the remediation, ensuring that credits reflect actual avoided emissions.

→ Read About “Refrigerant Leak Detection as a Service”

📌 Instead of being a one-off intervention, LDaaS is structured as a recurring service contract.

This creates alignment: project developers earn revenue from verified reductions, while operators save money from avoided refrigerant loss and system downtime.

Also, this is a verification step that will quantify impact, a further set of checks and balances to the process of private environmental governance.

Integrity Advantage: Source-Oriented Accounting

One of the persistent problems with refrigerant offsets, as we saw in Section 4, is the issue of aggregation without disclosure.

Gases are collected from multiple facilities, destroyed in bulk, but source-level claims remain opaque. Facilities can still report reductions in ESG filings, while credits are issued separately.

LDaaS addresses this by rooting credits in source-oriented, site-specific data. Each reduction is linked to a particular system, a particular leak, and a documented repair.

This provides exclusive ownership of claims — the customer (e.g., a grocer or warehouse) agrees not to count those identical reductions in ESG reports once they are converted into credits.

The transparency reduces the risk of double-counting, which undermines traditional destruction projects.

The Market Potential

Leak detection fits into the wider market evolution in three key ways:

High-Integrity Offsets

LDaaS creates credits that are both additional and event-based, meeting the criteria buyers now demand.

Corporate Insetting

Companies can choose to retain the reductions within their own supply chain, thereby strengthening their ESG performance without having to transact credits.

Policy Alignment

Many jurisdictions (e.g., EU F-gas regulation, U.S. AIM Act) are mandating leak detection and repair.

LDaaS programs can align with these policies, ensuring credits reflect not only voluntary action but also compliance reinforcement.

Lessons for Buyers and Sellers

For buyers, LDaaS-endorsed credits offer an opportunity to invest in prevention rather than cure. Destruction remains essential, but leak detection prevents emissions before they ever occur. For sellers, LDaaS is proof that market growth and integrity need not be at odds.

By linking revenue to data-rich, source-level verification, LDaaS creates offsets that withstand scrutiny, exactly the opposite of what sank CCX.

Why LDaaS Belongs in the Practical Guide

If Pearse & Böhm’s 2015 critique was that markets reward paper over performance, LDaaS is a direct response. It brings hidden emissions into the light, assigns exclusive ownership of reductions, and turns maintenance into measurable mitigation.

In this sense, it is not just a technical service — it is a structural reform, showing how carbon markets can evolve from commodification to accountability.

A Field Guide for Buyers and Sellers

A Decade’s Lesson: Bend vs. Shift

The decade behind us confirms what Pearse & Böhm warned in 2015: carbon markets, left unchecked, are structurally flawed. Weak rules, double counting, and the obsession with commodifying atmospheric reductions prevent them from delivering the radical decarbonization required. At best, they bend the curve; rarely do they shift it.

The failure of the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) is a cautionary milestone. Governance was loosened to drive transactions, protocols became too flexible, and integrity gave way to volume. The market collapsed, leaving behind not just financial losses but a profound erosion of trust. That collapse is not just history — it is a warning still relevant today.

The New Frontier: Accounting, Not Volume

The core of tomorrow’s market evolution is not a new offset type or a clever registry mechanism. It is better accounting. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), and other rule-making bodies are beginning to treat carbon in the same manner as financial accountants treat assets and liabilities: with standardized definitions, auditable records, and public disclosure.

This shift is decisive:

- Exclusive ownership rules prevent the double-counting that undermined CCX and voluntary markets.

- Auditable registries elevate credits from marketing claims to verifiable instruments.

- Mandatory disclosure brings climate performance into the same category as financial risk.

When carbon is accounted for on a balance sheet with the same rigor as revenue and debt, the games of inflated baselines and unverifiable promises disappear.

A Practical Field Guide

If Buying

- Retire credits transparently.

- Prioritize event-based, high-integrity programs (e.g., refrigerant destruction).

- Demand financial-grade accounting data.

- Beware of displacement and double accounting.

If Selling

- Issue only credits with exclusive claims.

- Invest in MRV systems that report both successes and failures.

- Avoid the CCX trap of chasing volume over rigor.

If Operating (Insetters and Corporates)

- Treat carbon performance as part of your financial audit.

- Build a carbon balance sheet aligned with FASB/ISSB guidance.

- Report reductions with the same honesty as financial performance — including underperformance.

The Road Ahead: 12, 24, and 48 Months

12 Months Out

- Expect sharper scrutiny from investors and auditors of carbon disclosures.

- Modeled, baseline-heavy offsets will lose market share.

- California’s disclosure regime will serve as a template for other jurisdictions.

24 Months Out

- Carbon data becomes an investor metric alongside EBITDA.

- Global standards (FASB, ISSB, EU taxonomy) converge on the concept of auditable disclosure.

- Registries align their crediting and retirement rules with generally accepted accounting principles.

48 Months Out

- Carbon markets bifurcate: low-integrity offsets fade, while credits that meet financial-grade accounting thrive.

- Corporate carbon balance sheets become standard practice in annual reporting.

- Integrity becomes the ultimate currency of climate markets.

Beyond Credits: Building Markets on Proof, Not Promises

Pearse & Böhm asked a blunt question: Can carbon markets deliver radical change?

A decade later, the answer is clearer: markets can bend the curve, but only integrity can shift it.

CCX showed the cost of weak governance. The rise of insetting and financial-grade accounting now shows us the way forward.

The decisive shift will not come from issuing more credits or multiplying registries. It will come when carbon is treated like debt; booked as a liability, subject to rigorous accounting, and backed by transparent disclosure.

That is how we avoid CCX’s fate, answer Pearse & Böhm’s critique, and move from bending the curve to transforming it.

This is where Leak Detection as a Service (LDAAS) becomes more than technology.

A detector may show the presence of a leak, but the act of verifying, recording refrigerant additions, and proving reductions is what ultimately alters the trajectory of a carbon credit.

LDAAS closes this trust gap, ensuring that credits rest not on promises but on auditable, verifiable tons retired.

- For buyers, this means demanding proof.

- For sellers, it means putting rigor before revenue.

- For insetters, it means embedding decarbonization into operations.

- For markets, it means recognizing that failure is not weakness but a sign the system is working.

Assuming 100% success is unrealistic, denials and corrections are how integrity takes root.

📌 If we follow these lessons, the next decade will not just bend the curve. It will shift it: building carbon markets on proof, not promises.