Unpacking the AIM Act: A Refresher for Owners on Compliance Essentials

Table of Contents

ToggleSeparating the Wheat from the Chaff: What Industry Proposals Won’t Change About the HFC Phasedown

Understanding the AIM Act and Its Impact

HFCs: A Law That’s Here to Stay – A Brief History of the AIM Act’s Enduring Mandate

In late 2020, amid rising climate concerns and surprising bipartisan unity, Congress passed the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act (AIM Act) as part of a larger appropriations package. With strong votes from both sides of the aisle, President Donald Trump signed the law on December 27, 2020.

This rare moment of cross-party consensus acknowledged the urgent need to phase down hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)—potent greenhouse gases used in everything from air conditioning to fire suppression. The Act also impacts heat pumps and the regulation of carbon dioxide levels.

The AIM Act sets an uncompromising target: an 85% reduction in the production and consumption of high-global-warming-potential HFCs by 2036. It achieves this by designating any saturated HFC with an exchange value (equivalent to its GWP) of 53 or higher as a regulated substance and mandating a step‑down allowance allocation program that tightens over time.

Because the AIM Act was enacted with robust bipartisan support and is codified into federal law, rolling it back isn’t as simple as issuing an executive order or a regulatory change. Amending or repealing such legislation requires a new bill to pass both the House and Senate and be signed by the President (or have a veto overridden)—a nearly insurmountable challenge in today’s divided political climate.

Moreover, the AIM Act aligns with broader international climate commitments (such as the Kigali Amendment), further cementing its role as a cornerstone of U.S. climate policy. In short, its bipartisan origins, statutory entrenchment, and global alignment make any rollback politically and legally arduous.

The importance of regulating carbon dioxide levels in cold chain management is also emphasized to ensure the safety and quality of temperature-sensitive products.

This history and framework illustrate that while regulatory tweaks may occur under EPA authority, the AIM Act’s fundamental mandate is designed to be a lasting element of our nation’s environmental policy landscape.

Are the Rules Related to HFCs Under Siege?

The AIM Act’s Ironclad Mandate vs. Regulatory Spin

In an era of rapid political shifts and uncertainty, it’s time to cut through the noise and expose the hard truths behind our nation’s fight against climate change. This provocative analysis unravels the AIM Act’s uncompromising mandate to phase down HFCs and contrasts it with proposals to tweak operational details. Here, we separate the non-negotiable statutory “wheat” from the negotiable regulatory “chaff,” empowering stakeholders to distinguish firm facts from conjecture.

I. Overview of the Refrigerant Phasedown Provisions in the AIM Act

The AIM Act directs the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to phase down HFCs—used in refrigeration, air conditioning, foam blowing, aerosols, and fire suppression—by reducing their production and consumption.

- 85% Reduction

The Act mandates an 85% reduction in the combined production and consumption of regulated HFCs relative to a baseline, with a target year generally set for 2036. This reduction is to be achieved via a step‑down allowance allocation program. - Mechanism

The EPA is instructed to establish a system of production/consumption allowances that will be reduced gradually until the 85% reduction target is met. - Affected Products and Uses

- Residential, commercial, and industrial air conditioning systems

- Refrigeration equipment (e.g., supermarkets, industrial freezers), where temperature monitoring and humidity levels are crucial for maintaining product safety and compliance

- Foam blowing agents

- Aerosol propellants

- Fire suppression systems

- Stakeholder Involvement

The Act includes provisions for public participation (petitions and comments) so that stakeholders can influence the process and ensure EPA responds within prescribed timeframes (typically within 180 days).

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

The implications of the AIM Act are profound for the cold chain industry.

Maintaining the integrity and quality of temperature-sensitive products throughout the entire supply chain process is crucial.

This includes ensuring proper handling, regulatory compliance, and the use of specialized equipment to safeguard perishable goods from potential spoilage and financial losses during transportation and storage.

Cold chains play a critical role in this process, with storage facilities being essential for maintaining the proper temperature control needed to ensure product integrity.

II. Detailed Breakdown of Key Provisions and Regulated HFCs

A. Regulated Substances and Criteria (Section 103)

The AIM Act defines a “regulated substance” as any saturated HFC (or its isomers not separately listed) with an assigned “exchange value” (equivalent to its global warming potential, or GWP) of 53 or higher.

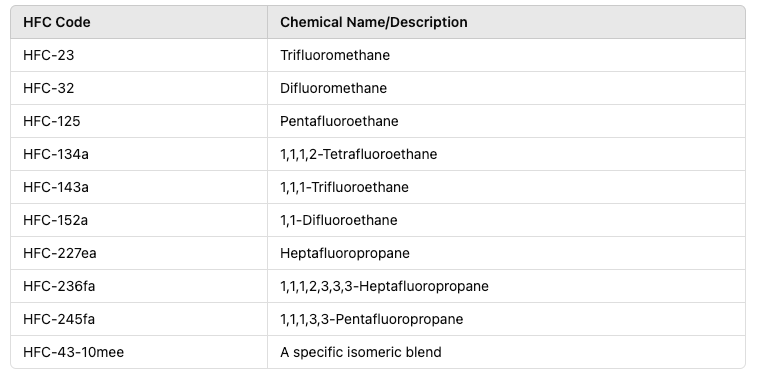

Although the Act does not list all 18 HFCs by name, subsequent EPA guidance has identified them as follows:

Each chemical is targeted because its exchange value meets or exceeds 53, significantly contributing to global warming.

B. Allowance and Consumption – Phase‑Down Schedule and Allowance Allocation (Section 103(d))

EPA must develop an allowance allocation program that gradually reduces permitted production and consumption levels of these HFCs. The overall goal is an 85% reduction relative to the baseline, with allowances stepping down over time until the target is reached by 2036.

C. Public Participation and Petitions (Section 104)

The Act provides a process for stakeholder engagement, ensuring that petitions for additional restrictions or modifications are publicly available and that EPA addresses these within a set period (typically 180 days).

III. Key Statutory Sections of the AIM Act

Section 103

- Contains the core mandates for restricting and phasing down HFCs.

- Section 103(c): Provides definitions and sets the exchange value threshold (53).

- Section 103(d): Directs EPA to establish an allowance allocation program to enforce the phasedown.

Section 104

- Outlines the procedures for public participation and the petition process.

While the AIM Act includes additional general provisions and definitions, Sections 103 and 104 are the pillars for the refrigerant phasedown.

IV. Refrigerant Management and Reporting

In the realm of cold chain management, the meticulous handling of refrigerants is paramount. The integrity of temperature-sensitive products, from perishable food to pharmaceuticals, hinges on effective refrigerant management and precise reporting.

These practices are not just regulatory requirements but essential elements that safeguard product quality and ensure the seamless operation of the supply chain.

Recent proposals aimed at adjusting existing Technology Transition regulations deployed in 2023 and Management Rules aim to refine the AIM Act’s framework with specific, operational changes. Below is a detailed breakdown:

The rollback of major laws, such as the repeal of Prohibition through the Twenty‐First Amendment in 1933, highlights the monumental challenge of completely reversing legislation after it has received bipartisan support. Repealing Prohibition required a constitutional amendment, showcasing the high political hurdles involved in overturning entrenched laws.

A law’s permanence post-passage reflects the reality that undoing it requires overwhelming consensus and significant political will—in this case, transformative shifts like constitutional amendments rather than just legislative revisions. Despite the difficulty of rolling back laws, that doesn’t stop people from proposing changes or hypothesizing about powers that may not exist.

While the repeal of Prohibition through the Twenty‐First Amendment in 1933 shows how hard it is to overturn a law with deep bipartisan support—requiring a constitutional amendment and massive consensus—it doesn’t stop people from proposing changes.

Despite the inherent difficulty of rolling back entrenched legislation like the AIM Act, various proposals have emerged in the last month. Although the EPA remains silent as the agency tasked with developing regulations, states are stepping in, and industry organizations are advocating for regulatory downgrades and extended compliance timelines to ease the transition.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

Proposed changes that relate to the Technology Transition Rule Asks: Specific Mathematical Considerations

GWP Limit Requests:

- Small Systems (< 200 lb): Set a GWP limit at 1400 to allow continued use of refrigerants 449A/448A through 2032, then transition to final rule limits after January 1, 2033. This cushions small systems from abrupt regulatory impacts—practical yet temporary.

- Large Systems (>200 lb): Set a GWP limit at 700 to permit the use of refrigerant 513A through 2032, with a shift to stricter limits post-2033. This proposal aligns with industry data for larger systems while remaining open to debate.

- HVAC Systems: Set a GWP limit at 2100 to allow continued use of R410 through 2032, then adopt final rule limits thereafter. This balances technology availability with environmental urgency, though it is likely to spark contention.

- Aerosol Products: Propose extending the compliance deadline from January 1, 2028, to January 1, 2030, using the assignment operator to set new regulatory values. This is a bid for greater market flexibility amid immediate compliance pressures.

Proposed changes to the Management Rule Subsection h

Appliances Regulated – Leak Repair and Detection

- Threshold Shift

Adjust requirements to apply only to appliances with a full charge of 50+ lbs of HFC (with a GWP of 700+) instead of 15+ lbs (with a GWP of 53+). This could reduce the burden on smaller appliances but might leave some emissions unaddressed. - HVAC Exclusions

Debate whether to exclude “light commercial HVAC” under a 50 lb threshold or all HVAC under a 15 lb threshold—a critical issue needing clear definitions.

Leak Repair Requirements

- Presumption of Failed Repairs

Eliminate the automatic presumption of failure if additional refrigerant is added within 12 months, unless it is due to the same leak—rewarding actual performance over arbitrary deadlines. - Extension Requests

Replace the rigid 30-day repair deadline with a “prompt” repair requirement, supported by progress reports if delays occur. Flexibility is key, though “prompt” must be defined clearly to prevent loopholes.

Leak Rate Thresholds and Calculations:

- Threshold Adjustments

Propose increasing thresholds to 25% for commercial refrigeration and 20% for HVAC compared to current levels. This may reduce inspection burdens but must balance environmental integrity. - Retrofit/Retirement Plans

Clarify that such plans are required only if the leak rate exceeds thresholds and the owner/operator opts not to repair, streamlining compliance processes.

Automatic Leak Detection Systems (ALDS)

- Compliance Dates and Thresholds

Propose a new compliance date of January 1, 2029, and raise the charge threshold for systems requiring ALDS from 1500 lbs to 2000 lbs—an industry-friendly change allowing more time for upgrades.

Reclaimed Refrigerant

Shift the deadline for using reclaimed refrigerant in select applications from January 1, 2029, to January 1, 2032, acknowledging current market supply challenges.

Third Party Vendors

Require vendors to provide repair and refrigerant-add records within 30 days of service completion to enhance transparency without imposing significant new burdens.

Chronically Leaking Appliances & Seasonal Variances

Limit CLA reporting requirements to appliances with charges over 50 lbs and revise the definition of seasonal variance so that refrigerant addition precedes removal—preventing overburdening of small systems and ensuring consistent reporting.

These are just a few of the proposed changes, the list is extensive, but regardless of the specifics, the details, or the ideas, the legislation stands and remains enforceable and although EPA has some latitude to make adjustments, they are very limited.

V. Implementation and Enforcement

The AIM Act’s mandate isn’t merely ink on paper—it’s a call to action backed by robust, built-in enforcement mechanisms that ensure its long-term impact:

Maintaining the integrity of temperature-sensitive goods is crucial, and the role of ‘called cool cargo’ in cold chain logistics cannot be overstated.

- Phased Allowance System

EPA has rolled out a graduated allowance allocation program, issuing and then systematically reducing production and consumption permits to secure an 85% reduction by 2036. This is a legally binding framework. - Monitoring and Audits

State-of-the-art monitoring systems, regular inspections, and rigorous audits will track HFC production and consumption. Deviations from mandated targets will trigger immediate corrective actions and penalties. The EPA was granted authority to deploy these regulations by a BiPartisan COobgress. - Transparency and Public Accountability

A strong public participation process ensures that all petitions and comments are on record, holding regulated parties accountable and driving enforcement with real-world data. The EPA followed the guidance set onto them by Congress. - Legal and Regulatory Backstop

With enforcement powers rooted in law, rolling back or ignoring the mandate is nearly impossible without a full legislative overhaul—an extremely unlikely scenario in today’s political climate.

It is Common and expected for states to join the enforcement activity to ensure the AIm Act is put into motion. There are 21 states part of this group.

VI. What should you be doing to get ready?

For industry leaders and operators, the compliance train has already left the station:

There is a cliff in 2036 that will result in a complete shutdown in access to any refrigerant with a GWP 53 and over. If as an industry everything from a portable air cooling unit to a Data Center Cooling system and all the devices delivering cold food, seafood, medical supplies, and comfortable homes needs a transition, then the only way to safeguard this critical industry is to

- Adopt Proactive Monitoring

Invest in robust tracking systems and modern monitoring technologies to keep real-time tabs on HFC usage and emissions. - Implement Regular Maintenance & Leak Management

Establish a rigorous maintenance schedule with timely leak detection and repair. Prioritize technologies that automatically monitor and report leak rates. - Upgrade to Low-GWP Alternatives Early

Transition sooner to lower-GWP refrigerants and technologies, positioning your operations as environmental leaders. - Thorough Documentation and Transparent Reporting

Keep meticulous records of all maintenance, inspections, and repairs to demonstrate compliance and streamline regulator interactions. - Increment and Decrement Compliance Measures Using Unary and Logical Operators

Apply incremental adjustments to compliance measures as needed, ensuring efforts are continuously developed and fresh. Operators should set various compliance metrics, keeping the degtails and policy awareness to to true, false, or null results to enhance team engagement and decision-making processes. - Invest in Training and Certification

Ensure technicians and operators are trained on the latest technology & compliance requirements and best practices; certification programs can standardize practices and reduce risks. - Engage with Stakeholders

Actively participate in the public process. Provide feedback and engage with EPA on regulatory updates to help shape future rules and ensure your concerns are heard.

By embracing these practices, regulated entities can transform compliance from a bureaucratic burden into a competitive advantage—turning environmental responsibility into an engine for innovation.

Should we worry about temperature-sensitive products and food deserts that result from the Aim Act regulations?

Food product quality, dairy products, and things that rely on a deep freeze, like frozen foods and cool cargo are all part of the Cold Chain and the Transition to Alternative Technologies. Smaller markets in regions around the US, are responsible for meeting the regulations just like the big guys.

There is help for this group that has less acccess to capital and Vermont Energy Investment Corporation or VEIC which is a non-profit organization based in Vermont that seeks to reduce the economic and environmental costs of energy consumption through energy efficiency and renewable energy adoption.

They have been helping smaller grocers and food cooperatives make the transition but they need more resources and help.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

VII. The AIM Act: A Republican-Led, Unyielding Climate Commitment

The AIM Act, also known as the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act, is a landmark legislation demonstrating the Republican Party’s commitment to addressing climate change:

Sponsorship and Firm Commitment:

- Primarily championed by Republican lawmakers—most notably Senator John Kennedy of Louisiana and Senator Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia—the Act was crafted with unyielding language to safeguard its core mandates.

- Through bipartisan negotiations, key provisions (such as the 85% reduction in HFC production and consumption by 2036) were insulated from political interference.

- The language ensures strong long-term enforcement, prohibiting any future dilution of decarbonization goals without a full legislative overhaul.

Bipartisan Support—But Republican Roots

- Although the Act secured bipartisan votes, its substance is rooted in a Republican vision of market-driven climate policy.

- It provides “tough but achievable” emissions reduction targets while allowing industries a manageable transition, aligning with international commitments like the Kigali Amendment.

VIII. Final Analysis – Separating the Wheat from the Chaff

📌 In conclusion

The AIM Act is an unshakeable, Republican-led legislative fortress mandating an 85% reduction in high-GWP HFC production and consumption by 2036. . This is the difference between companies reacting to regulations and those leading to operational excellence.

Its core features include:

The Immutable Statutory Core (The “Wheat”)

Regulated HFCs: Every saturated HFC with an exchange value (GWP) of 53 or higher is regulated.

Phase-down Target: The non-negotiable 85% reduction in production and consumption by 2036, enforced through a graduated allowance program.

Stakeholder Engagement: A robust process ensuring transparency and public participation.

The Evolving Details (The “Chaff”)

Operational Specifications

Detailed proposals (tailored GWP limits, revised leak repair protocols, adjusted compliance timelines) are currently under debate.

Industry Dynamics

While some adjustments (such as extended deadlines or raised charge thresholds) are practical, others (like redefining HVAC categories or altering leak rate calculations) remain contentious and may be refined further.

Unshakeable Mandate, Unstoppable Future

The AIM Act isn’t just another law—it’s a bold, bipartisan declaration that high-GWP HFCs are out and climate responsibility is in.

Its 85% reduction target by 2036 is set in stone, and its provisions are designed to be resilient against political shifts. While the finer operational details may continue to evolve, the core mandate is here to stay, forming the backbone of U.S. climate policy.

This comprehensive analysis separates the immutable statutory “wheat” from the evolving regulatory “chaff,” empowering stakeholders to distinguish firm, non-negotiable mandates from proposals that remain in flux.

As the AIM Act shapes our environmental policy, its lasting impact is assured—ushering in a future where potent greenhouse gases become relics of the past.

For full details, refer to the official text of the AIM Act on congress.gov.