Don’t Get Fooled by Numbers: How Refrigerants and Scope 1 Reporting Spot Red Flags in a Company’s Balance Sheet

Introduction: The Illusion of Financial Health and Carbon Footprint

Would you trust a financial statement that showed revenue, assets, and profit but ignored a massive operational flaw that silently drained cash every year?

This is precisely what happens when companies fail to account for refrigerant leaks, energy waste, and emissions-related inefficiencies in their financial statements. Although these issues don’t appear as line items, they directly impact operating costs, regulatory risks, and long-term profitability. Failing to report carbon emissions can also obscure an organization’s financial health.

At the same time, business leaders often view regulations as a burden rather than an operational advantage. But the reality is:

🚨 Regulations don’t create inefficiencies—they expose them.

🚨 Financial statements don’t reflect operational waste until it becomes a crisis.

🚨 The best businesses don’t just comply with regulations—they leverage them to improve efficiency, extend equipment life, and reduce financial risk.

The best run companies treat emissions tracking, refrigerant management, and energy efficiency as core business strategies—not just compliance obligations. Companies can mitigate operating costs and reduce regulatory risks by accurately calculating and managing direct emissions.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

Woolworths’ Smart Refrigeration Strategy

Woolworths, the Australian supermarket giant, is one of the best-run companies in emissions tracking, refrigerant management, and energy efficiency. Woolworths recognized early on that treating emissions management as a business strategy—not just a compliance requirement—could deliver operational cost savings, regulatory advantages, and sustainability benefits.

How Woolworths Integrated Emissions Tracking & Refrigerant Management Into Operations

✅ Proactive Refrigerant Leak Detection:

Instead of waiting for leaks to hit regulatory thresholds, Woolworths implemented automated leak detection systems to monitor refrigerant emissions in real time. This prevented excessive loss, reduced repair costs, and kept their cooling systems operating efficiently.

✅ Energy Efficiency as a Cost-Reduction Strategy:

Woolworths optimized refrigeration systems, retrofitted stores with CO₂-based refrigerants and improved energy efficiency in cold storage. This led to a 37% reduction in energy consumption across their stores.

✅ Regulatory & Financial Benefits:

By accurately tracking direct emissions and staying ahead of refrigerant phase-down policies, Woolworths avoided regulatory fines and gained access to better financing terms due to lower environmental risk.

📌 Key takeaway

Woolworths didn’t just treat refrigerant emissions and energy tracking as a compliance checkbox—they used it as a business tool to drive efficiency, reduce costs, and gain a competitive edge. This is the difference between companies reacting to regulations and those leading to operational excellence.

I. Why Regulations Exist: A Response to Operational Failures

Regulations exist because businesses have historically ignored operational inefficiencies until they became too costly to ignore. The average system leaks or loses 25% of its charge annually. This is just one example of many. The problem is so big that a group that initially helped solve the Exxon Valdez crisis took it on and established the GHG Protocol. This foundational framework provides guidelines for measuring and managing greenhouse gas emissions across various scopes.

One of the biggest misconceptions is that regulations like the EPA refrigerant phase-down or EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) are punitive measures, but they help businesses establish structured frameworks for managing refrigerant leaks and emissions and create a level playing field for competing in a global economy.

Regulatory Definitions & Why They Matter

There are so many new words and terms that it’s important to understand what we are talking about. So here are a few key ones you should know.

📌 Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD):

A European Union law requiring companies to identify, prevent, and disclose environmental impacts, including refrigerant leaks, across their supply chains.

✔ Forces companies to document and manage Scope 1 & 2 emissions

✔ Mandates clear operational policies for emissions reduction

✔ Penalizes non-compliance with financial and legal consequences

📌 SEC Climate Disclosure Rule:

A U.S. regulation requiring publicly traded companies to report emissions data and climate-related risks in their financial statements.

✔ Requires companies to disclose energy consumption & refrigerant loss data

✔ Ensures investors fully understand hidden financial risks

📌 ISO 14064 (Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reporting):

A global framework for measuring and tracking refrigerant emissions.

✔ Helps businesses establish emissions baselines

✔ Improves credibility and transparency in sustainability reporting

✔ Introduces the concept of global warming potential (GWP), which allows for the comparison of the warming impacts of various gases relative to carbon dioxide. This provides a standardized method for reporting and calculating emissions from different sources, particularly refrigerants and industrial processes.

📌 ISO 14001 (Environmental Management Systems):

A structured environmental performance standard that helps companies improve sustainability and cut operational waste.

✔ Encourages preventative leak detection

✔ Establishes structured maintenance plans for refrigerant systems

📌 California Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act is the combo climate and reporting accountability and Climate-Related Financial Risk Act.

SB 253

- Requires US businesses with more than $1 billion in annual revenue to report their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

- Requires companies to report their emissions for 2025 in 2026, and for 2026 in 2027

- Requires companies to get third-party assurance of their reports

- Requires companies to report on a digital platform that makes the information public

- Allows companies to comply with other regulatory reporting that meets equivalent standards

SB 261

- Requires US businesses with more than $500 million in annual revenue to report on their climate-related financial risks and mitigation strategies

- Requires companies to report on these risks twice a year

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

📌 The EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) is a European Union (EU) law requiring companies to address environmental and human rights impacts.

The CSDDD went into effect on July 25, 2024.

There are more terms, and I could write a whole story about this, but this starter section might open some eyes and bring some awards to the growing scope of regulations. Places like NY, Colorado, and many others will likely set their own policies and if you wondering why these states care or would invest in this effort, it’s because they recognize that without some rules, commercial markets struggle to protect shareholders

State regulations play a crucial role in safeguarding shareholders and ensuring the smooth operation of commercial markets. Without appropriate rules, markets may struggle to protect investors’ interests, leading to potential instability and loss of confidence. For instance, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforces laws that broadly prohibit fraudulent activities concerning the offer, purchase, or sale of securities, thereby maintaining market integrity and protecting shareholders.

Additionally, the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 was enacted to enhance corporate governance and strengthen companies’ accountability to their shareholders. This federal law introduced stringent reforms to improve financial disclosures and prevent corporate fraud, thereby bolstering investor protection.

Moreover, state-level regulations, often called “blue sky laws,” are designed to protect investors from securities fraud. They require sellers of new issues to register their offerings and provide financial details. These laws enable states to oversee securities offerings and sales, ensuring that investors have access to accurate information before making investment decisions

Federal and state regulations are essential in establishing a framework that protects shareholders and maintains the integrity of commercial markets. Without such rules, markets would face challenges in preventing fraudulent activities and ensuring fair practices, ultimately undermining investor confidence and market stability.

One example of rules and regulations that are driven by market activity is the ISO international standards, which provide businesses of all sizes and industries with a structured framework to reduce costs, improve efficiency, and expand into new markets. For small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), these standards offer key advantages, including:

- Enhancing Customer Confidence – Demonstrating that products and services meet high safety and reliability standards.

- Ensuring Regulatory Compliance – Helping businesses meet legal and industry requirements more efficiently and cost-effectively.

- Boosting Operational Efficiency – Standardizing processes to improve productivity and reduce waste.

- Facilitating Market Access – Aligning with global best practices to compete in international markets.

Standards adopted by regulators and become law behave the same but follow different paths to adoption.

Standards, regulations, and processes strengthen customer and market confidence, and those that perform the best gain the best market position, reduce risks, and build long-term resilience in an increasingly competitive business environment.

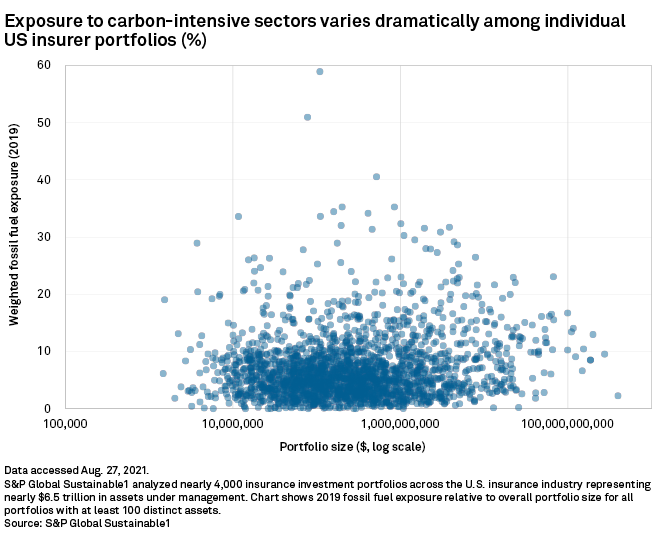

II. The Story Behind Scope 1, 2, & 3 Emissions Factors

The initiative that started tracking emissions in 1997 was the businesses and governments, which sought to understand the scale, scope, and challenges of monitoring emissions. But soon you will see they were motivated by well-established segments of their economies.

My exposure to this topic came from a free seminar run by the Treasury Department or the Federal Reserve in Boston. I’m unsure which one, but it was hosted at the Federal Reserve building in Boston in 1998. There was a speaker from an insurance company. He was talking about how, as an insurer, they saw climate as a bigger deal, a more present topic on their balance sheet, and that whether we believed in the science did not matter to them and that they were going to make sure that it ended up in the balance sheets of their clients

…” they were upping their rates to account for floods, more car accidents due to roads in the south that were not “winter ready” and even that roofs in England were built for rain to run off them but not snow to stick, so the roofs on older buildings would cost more to insure”

They talked about how they were pushing for changes to building codes so that future owners would have less risk, and they, as an insurer, would also have less risk. Then he shared some detailed financials, but I was mesmerized that lurking in the background was this financial engine driving change I COULD NOT have imagined. So this is the story of accountability, not some NGOs that eat tofu.

Around that time, scientists and policymakers increasingly recognized the impact of industrial activities on global warming, and insurers and banks wanted to know their exposure. Burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes released massive amounts of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change, but to what extent? No one knew? Climate science was a new topic, and no one was studying this stuff… yet.

Despite mounting evidence, businesses and industries had no standardized way to measure or report emissions. Without clear data, governments, investors, and even companies had little understanding of their carbon footprint, how to manage it, or even what it meant.

When It Started: The Late 1990s and the First Global Climate Commitments

The Kyoto Protocol, signed in 1997, was the first international treaty to require countries to set targets for reducing GHG emissions. However, while governments were setting national carbon reduction goals, businesses—one of the most significant sources of emissions—had no established standard to measure impact or even identify GHG emissions factors.

To fill this gap, the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) partnered in 1998 to develop a global standard for measuring and reporting corporate emissions. This initiative became the GHG Protocol, which remains the world’s leading framework for corporate emissions accounting today.

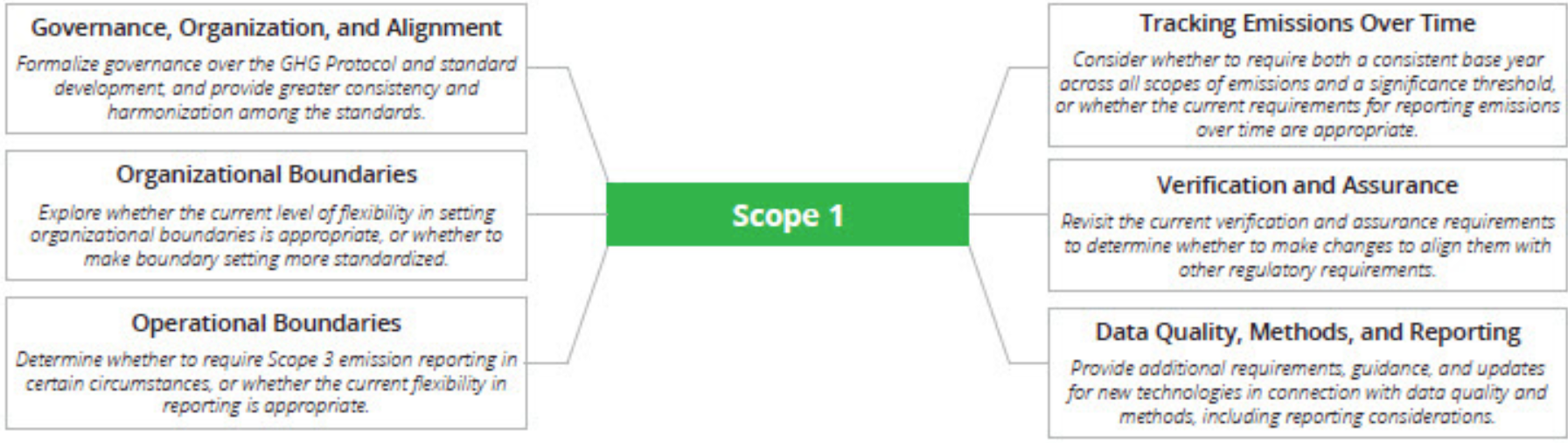

How It Took Shape: The Development of the GHG Protocol and Three Scopes

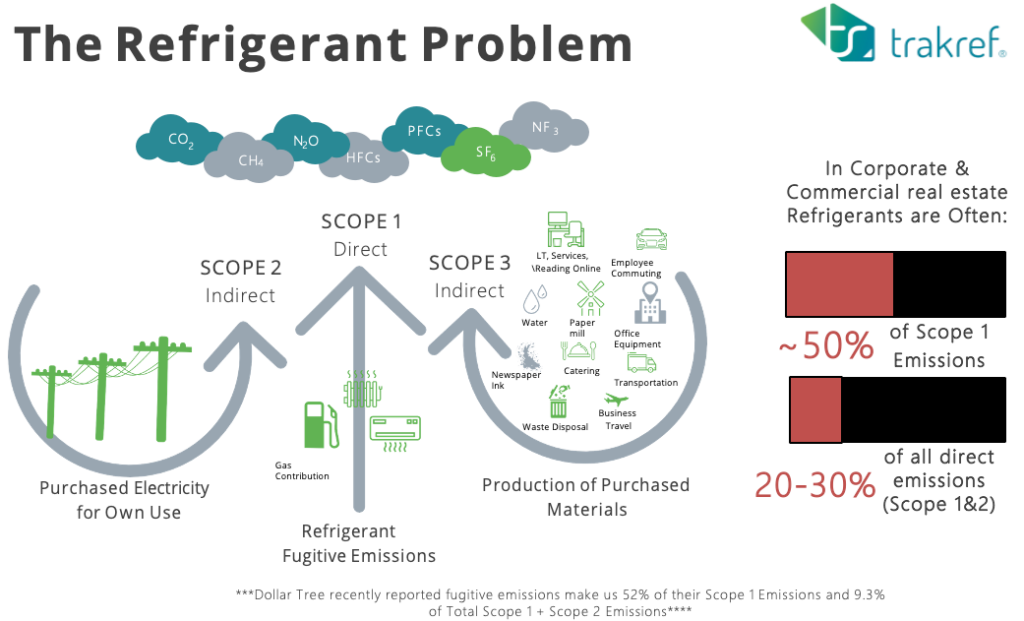

GHG Protocol introduced a standardized approach for companies to measure emissions across their entire value chain. To make reporting clearer, it categorized emissions into three scopes:

- Scope 1 – Direct emissions from company-owned sources (e.g., factory emissions, fuel burned in company trucks).

- Scope 2 – Indirect emissions from purchased electricity, heat, and cooling (e.g., the electricity used in offices or manufacturing facilities).

- Scope 3 – Indirect emissions from supply chains and product use (e.g., emissions from suppliers, transportation, and how customers use a product).

This structure created a universal way to track and compare emissions across industries, laying the foundation for corporate climate responsibility.

Who Drove the Initiative? Businesses, Insurance Companies, and Financial Institutions

As climate awareness grew, so did pressure from multiple stakeholders:

- Governments began integrating emissions tracking into regulations, starting with voluntary programs and evolving into mandatory disclosure laws (e.g., EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), California’s Climate Accountability Act).

- Businesses saw a need to manage climate risks and improve efficiency—energy waste and emissions often signaled operational inefficiencies.

- Investors and financial markets started demanding better transparency on climate risks, pushing companies to disclose emissions alongside financial statements.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

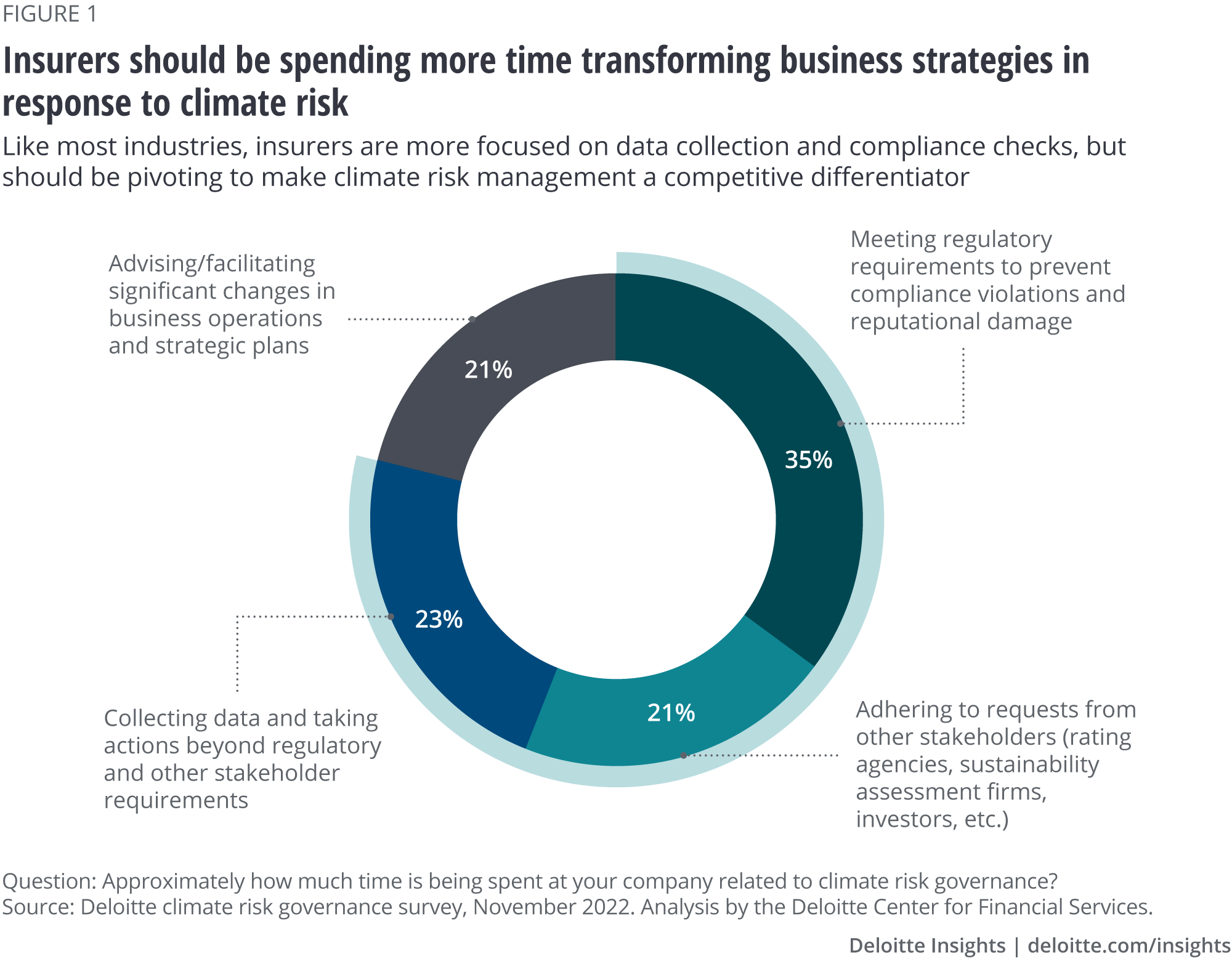

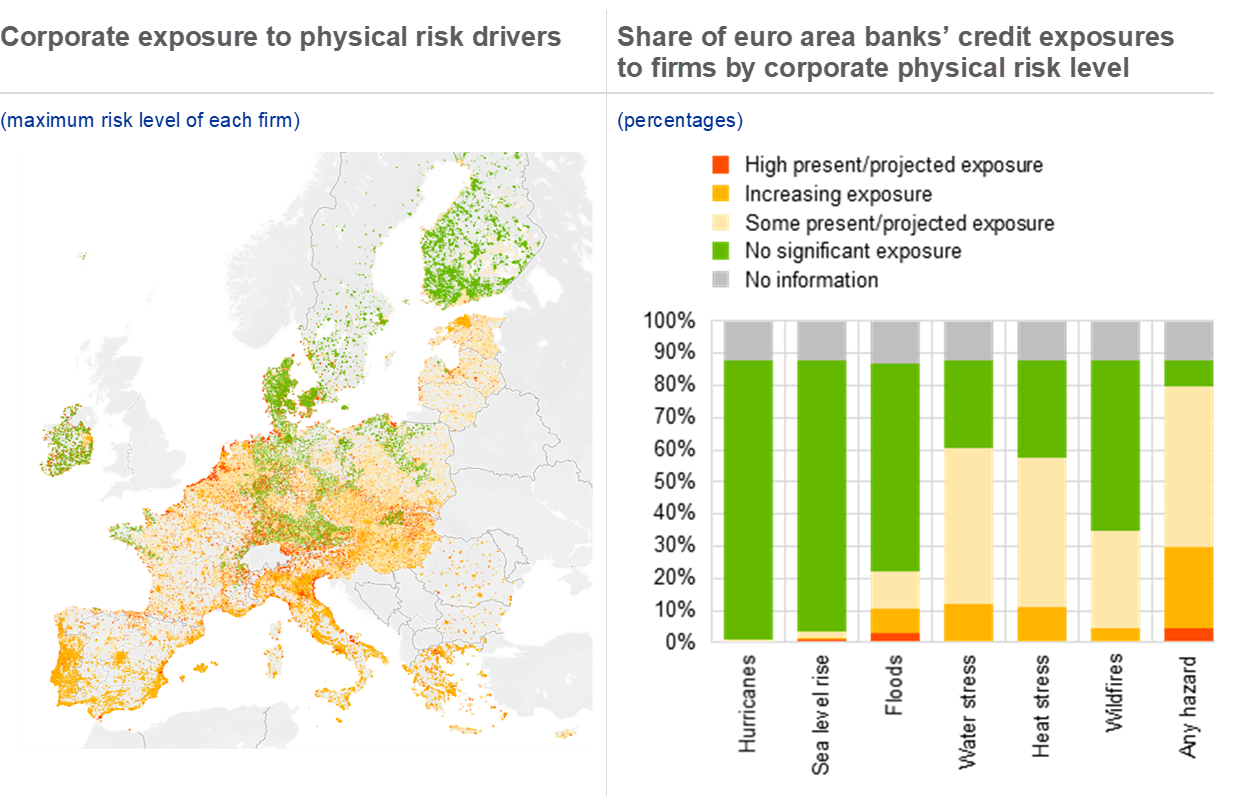

How & Why Insurance Companies Made Carbon Emissions a Financial Risk

Insurance companies have always been involved in assessing and managing risk. Historically, they focused on tangible risks like fires, floods, and property damage. But by the late 20th century, climate change emerged as a new category of risk—one that posed long-term financial threats to their business models.

Insurance Companies Cared About Measuring GHG Emissions because…

By the 1990s, insurers were already seeing the financial impacts of climate change:

- Increased frequency and severity of natural disasters (hurricanes, floods, wildfires) were leading to massive payouts on insured assets.

- Supply chain disruptions from extreme weather events affected insured businesses, causing loss of revenue and damages.

- Regulatory risks were emerging, with governments considering policies that could reshape industries and impact insured companies’ liabilities.

For insurers, these growing climate risks were not theoretical but financial liabilities. If they could quantify the carbon emissions that contributed to climate change, they could better predict the long-term risks they were insuring against.

How Insurance Companies Got Involved in GHG Accounting

As the Kyoto Protocol (1997) set the stage for international climate action, insurers realized they needed a standardized way to measure emissions exposure—both for their financial planning and to assess risk in the industries they insured.

They played a key role in pushing for:

- A global standard for measuring corporate emissions—Without a unified framework, comparing emissions across industries and regions was impossible. Insurers supported the development of the GHG Protocol, launched in 1998 by the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD).

- Emissions disclosures as a financial risk factor—Insurers advocated for emissions data to be included in corporate financial reports, as they are directly correlated with future liabilities.

- Climate modeling for risk assessment – By integrating emissions data into risk models, insurers could better estimate potential losses from climate-related damages and adjust their underwriting strategies accordingly.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

What This Meant for Businesses

With insurance companies demanding better emissions data, businesses faced new financial pressures:

- Higher premiums for high-emissions industries – Companies with high carbon footprints (e.g., heavy manufacturing, oil & gas, transportation) saw rising insurance costs.

- More stringent risk assessments – Insurers started factoring emissions-related climate risks into their underwriting decisions, influencing corporate investment strategies.

- Investor pressure – As insurance companies aligned with institutional investors on climate risks, businesses faced mounting expectations to track, report, and reduce emissions.

Long-Term Impact on GHG Accounting (and accountability)

- Emissions tracking became an essential tool for managing financial risk—not just an environmental issue- thanks to early pressure from insurers. This helped drive:

- The integration of climate risks into corporate financial disclosures (e.g., the SEC Climate Disclosure Rules, and the EU’s CSRD).

- More sophisticated climate risk models used by insurance firms, banks, and investors.

- Higher premiums for companies failing to manage emissions, reinforcing the financial case for sustainability.

Insurance companies played a critical and often overlooked role in developing the GHG Protocol. Their need to quantify and price climate risks drove the push for standardized emissions reporting. Today, their influence continues. Companies that fail to manage emissions face regulatory and investor scrutiny, higher insurance costs, and reduced access to coverage in a world where climate risks are no longer abstract but financial realities.

By the early 2000s, major corporations, financial institutions, and policymakers had embraced GHG accounting as a tool for climate action and economic decision-making.

- Emissions from company-owned vehicles and equipment: This includes the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases emitted by the company’s trucks, cars, and machinery.

- Emissions from on-site fuel combustion: Boilers, generators, and other equipment that burn natural gas or other fossil fuels on-site contribute significantly to Scope 1 emissions.

- Emissions from industrial processes: Industries such as cement and steel production release substantial amounts of greenhouse gases during their production processes.

- Fugitive emissions from refrigeration and air conditioning equipment: Leaks from refrigerants used in cooling systems can release potent greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

How the Business World Adapted

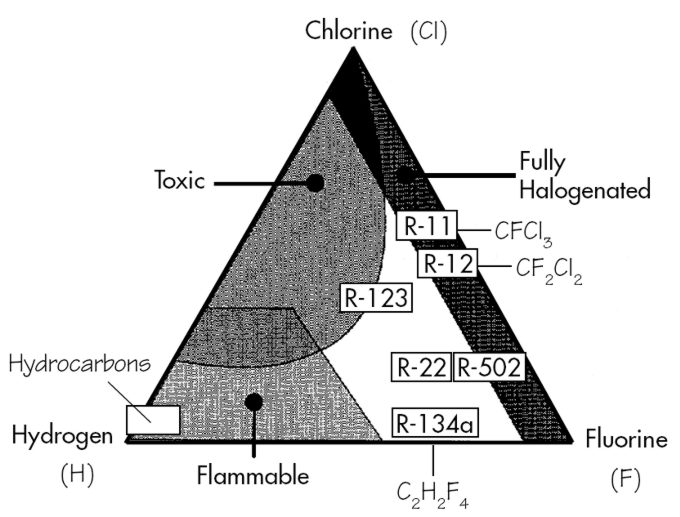

Back in the 90’s before Climate Change was a science, and uncertainty was everywhere, the EPA and the chemical companies selling refrigerant with names like DuPont, Allied Signal, ICI Klea were using 3 simple metrics when choosing a refrigerant

- Toxicity

- Flammability

- Ozone Depleting Potential – look at the Halogenated side of the

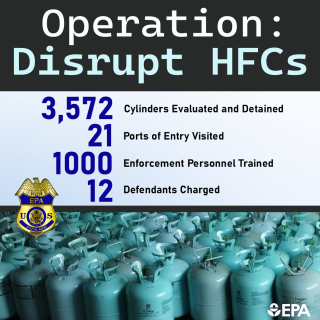

I visited the EPA, the state Department and AHRI, numerous times in the 90’s and early 2000’s even joining the AHRI Chemical and Reclaim Committee and participating in annual industry gatherings to promote three things that were ignored, because they were not needed, 1) a refrigerant score card to hekp people make better decision about the new 4th dimension of refrigerants 2) tagging and labelling refrigerant cylinders to slow the illegal imports that were undermining our refrigerant supply chian 3) changing the reclaim industry testing standards – this was messy, sincve the chemical companies had influenced ERA to adopt the AHRi virgin gas standard which was now applied to reclaim, causing many comapneis to incorrectly categorize reclaim returns from customers as mixed.

EPA had no mandate, no motivation and no interest in the Carbon Issues, they sent me to the State Department, responsible for handling international treaties, and ultimately I ended up at the Dearment of Energy in a specail program called 1605b

The Overlooked Alternative: How HFOs Were Initially Ignored in Favor of HFCs

The Early Days of the CFC Phaseout: A Focus on HFCs

When the Montreal Protocol (1987) triggered the phaseout of ozone-depleting substances (ODS) like CFCs and HCFCs, regulators and industry leaders scrambled to find viable replacements. The immediate concern was ozone depletion, not global warming, so the focus was on refrigerants that could replace CFCs without damaging the ozone layer.

At the time, HFCs (Hydrofluorocarbons) seemed like the perfect solution:

✔ No chlorine, meaning zero ozone depletion potential (ODP).

✔ Similar performance to CFCs, making them easy to adopt with minimal retrofits.

✔ Non-toxic and non-flammable, which made them safer than alternatives like ammonia and hydrocarbons.

As a result, both the EPA and the refrigeration industry largely ignored HFOs (Hydrofluoroolefins) in the early days. The regulatory and scientific community viewed HFCs as the “silver bullet” solution—a necessary step to transition away from CFCs and HCFCs.

Why HFOs Were Initially Overlooked

HFOs existed as a possible alternative but were not seriously considered for several reasons:

- The Urgency to Eliminate Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODS)

- The priority in the 1990s and early 2000s was eliminating CFCs and HCFCs as quickly as possible.

- HFCs provided an immediate, scalable drop-in replacement that the industry could adopt without major overhauls.

- Lack of Awareness of Global Warming Potential (GWP)

- Climate science linking refrigerants to global warming was still developing.

- Policymakers focused on ozone protection, not the greenhouse gas impact of refrigerants.

- HFOs Were More Expensive & Unproven at the Time

- Early HFO production was expensive, making them economically unviable for large-scale adoption.

- The industry needed a “sure bet,” and HFCs had already been tested and validated for performance.

- No Immediate Regulatory Pressure to Reduce GWP

- The Kyoto Protocol (1997) recognized HFCs as greenhouse gases but didn’t mandate their reduction.

- The EPA, EU, and global regulators didn’t prioritize HFC phase-downs until the 2010s.

- Industry Hesitation to Shift Again

- After investing billions in HFC-based systems, manufacturers and businesses weren’t eager to transition yet again to another refrigerant class.

- The assumption was that HFCs would be the long-term solution, despite growing climate concerns.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

The Turning Point: Why HFOs Became the Focus Later

By the late 2000s and early 2010s, the climate impact of refrigerants could no longer be ignored:

✔ HFCs were found to be major greenhouse gases, with GWP values hundreds to thousands of times higher than CO₂ (e.g., R-134a has a GWP of 1,430).

✔ The Kigali Amendment (2016) to the Montreal Protocol mandated an HFC phasedown, forcing industries to find alternatives.

✔ HFOs re-emerged as a viable replacement, offering ultra-low GWP while maintaining performance.

This shift mirrored the earlier CFC-to-HFC transition—but this time, climate change was the driver rather than ozone depletion.

The Consequences of Overlooking HFOs Early On

Had HFOs been prioritized earlier, industries could have avoided:

🚨 The need for two separate transitions (CFCs → HFCs → HFOs).

🚨 Massive investments in HFC-based systems that are now becoming obsolete.

🚨 Unnecessary emissions that worsened global warming over the past 30 years.

Final Takeaway

The EPA and the refrigeration industry initially viewed HFCs as the final answer, failing to anticipate their long-term environmental impact. HFOs were overlooked due to cost, lack of urgency, and regulatory blind spots. However, as the global climate crisis intensified, HFOs became the inevitable next step—proving that businesses and policymakers often focus on short-term fixes rather than long-term sustainability.

The 1605(b) Program: The Foundation for Voluntary Greenhouse Gas Reporting and Its Evolving Role in Refrigerant Emissions Tracking

The Evolution of 1605(b): How a Voluntary Climate Program Paved the Way for Refrigerant Emissions Reporting

In the early 1990s, climate policy was still in its infancy. While scientists warned of rising greenhouse gas (GHG) levels, the idea of regulating carbon emissions was politically contentious. Businesses, especially in the energy and manufacturing sectors, feared mandatory controls would stifle economic growth. At the same time, insurance companies and financial institutions were beginning to see the long-term risks of climate change—more frequent natural disasters, rising asset losses, and growing liabilities.

Amid this debate, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act of 1992 (EPAct 1992), a sweeping bill aimed at enhancing U.S. energy security, improving efficiency, and setting the foundation for renewable energy investment. Buried within its provisions was a small but significant program: Section 1605(b), the Voluntary Reporting of Greenhouse Gases Program. Unlike later regulatory initiatives, 1605(b) was framed as an incentive-based system, encouraging businesses to voluntarily track and disclose their GHG emissions.

A Bipartisan Effort to Promote Transparency, Not Regulation

The 1605(b) program was crafted as a compromise between environmental advocates and business interests. Key legislative sponsors included:

- Senator J. Bennett Johnston (D-LA) – Chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Johnston was a key architect of EPAct 1992. Representing Louisiana, a state with a strong oil and gas industry, he balanced environmental concerns with industry interests, ensuring the program remained voluntary.

- Representative Philip Sharp (D-IN) – A leading energy policy expert in the House, Sharp believed businesses needed incentives, not mandates, to track emissions. His work ensured 1605(b) would serve as a preparatory step for future regulations, rather than an immediate compliance burden.

- Senator Malcolm Wallop (R-WY) – Representing a coal-heavy state, Wallop championed market-driven approaches to environmental challenges. He saw voluntary reporting as a way for businesses to demonstrate good faith without the need for federal enforcement.

Their vision was clear: Give businesses a chance to track emissions on their own terms, before stricter policies became necessary.

Why the Program Was Placed Under the DOE Instead of the EPA

Unlike traditional environmental regulations, which were typically overseen by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the 1605(b) program was housed within the Department of Energy (DOE). This decision was intentional.

At the time, carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other greenhouse gases like refrigerants were not yet classified as pollutants under the Clean Air Act. The EPA primarily focused on air quality and ozone-depleting substances (ODS), such as CFCs and HCFCs, under the Montreal Protocol. In contrast, the DOE was already responsible for tracking national energy use and industrial efficiency, making it the natural home for a program centered on voluntary emissions reductions.

The DOE’s mission aligned with the program’s goals:

- Encourage businesses to reduce emissions through energy efficiency improvements.

- Track national emissions trends without imposing regulatory burdens.

- Allow industries to experiment with emissions reporting before it became mandatory.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

How Industry Influenced the Program’s Design

The voluntary nature of 1605(b) was largely shaped by business and industry groups, who lobbied against mandatory reporting. Their argument was that market-driven solutions would be more effective than federal mandates.

- Electric Utilities – Companies like Duke Energy and Pacific Gas & Electric saw emissions reporting as a way to build credibility with investors without committing to costly regulatory compliance.

- Oil & Gas Companies – Firms like ExxonMobil and Chevron recognized that tracking emissions could help them prepare for future regulations without immediate financial penalties.

- Manufacturers & Chemical Companies – The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) and the American Chemistry Council resisted strict GHG rules, but acknowledged that early tracking could inform their long-term sustainability strategies.

- Insurance & Financial Institutions – Reinsurance companies like Swiss Re and Munich Re were among the first financial players to push for GHG disclosure, seeing climate change as a growing liability.

This industry influence meant that 1605(b) remained strictly voluntary, lacking enforcement mechanisms but laying the foundation for the corporate climate disclosures we see today.

The Unexpected Role of Refrigerants in the 1605(b) Program

At its inception, 1605(b) did not explicitly address refrigerants like (R-22) or hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). The focus was on energy-related emissions, such as CO₂ from power plants, methane from oil and gas operations, and nitrous oxide from industrial processes.

Refrigerants, at the time, were seen primarily as an ozone problem, not a climate issue. The EPA was already phasing out ozone-depleting substances (ODS) like CFCs and HCFCs under the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, so refrigerants were largely omitted from DOE’s climate tracking efforts.

However, this perspective began to shift in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The Turning Point: Recognizing Refrigerants as Greenhouse Gases

As the owner of a refrigerant reclaim plant (Polar Technology) I began to work with DOE’s Office of Policy and International Affairs raising concern that HFCs—the supposed “safe” replacements for ozone-depleting refrigerants—had high global warming potential (GWP). Unlike CO₂, which stays in the atmosphere for centuries, HFCs could trap thousands of times more heat per molecule, making their climate impact disproportionate.

- The Kyoto Protocol (1997) classified HFCs as greenhouse gases.

- Insurance companies began treating refrigerant leaks as a financial risk, recognizing that leaks led to higher energy costs and potential regulatory liabilities.

- Investors and financial analysts started demanding more transparency on refrigerant-related emissions, as part of broader climate risk assessments. Burdens placedon them by the insurers and financial institutions.

As a result, the DOE expanded 1605(b) reporting guidelines to encourage companies to account for high-GWP refrigerants, including:

- HCFCs like R-22 – Initially phased out under ozone regulations but later recognized as a climate risk.

- HFCs like R-134a – Marketed as climate-friendly but found to be potent greenhouse gases.

- PFCs & SF₆ – Included due to their extreme GWP levels, particularly in industrial applications.

While reporting remained voluntary, businesses that participated in 1605(b) were among the first to systematically track refrigerant emissions, setting the stage for adoption across the entire industry.

The Lasting Impact of the 1605(b) Program

Though it was never a regulatory tool, 1605(b) played a critical role in shaping how businesses approach emissions reporting today. Its legacy includes:

- The GHG Protocol & ISO 14064, which now require refrigerants to be reported under Scope 1 emissions.

- The SEC Climate Disclosure Rule (2024), which mandates disclosure of material refrigerant emissions.

- State and federal policies that restrict high-GWP refrigerants, making tracking and reporting essential for compliance.

- Financial risk integration, as insurers and investors penalize companies that fail to manage refrigerant-related risks.

F1605(b) Was a Stepping Stone, Not the Endgame

At the time, 1605(b) was seen as a compromise—an alternative to stricter regulations. But in reality, it was an essential stepping stone toward today’s climate disclosure rules.

- It gave companies a head start on emissions tracking, helping them prepare for the regulations that followed.

- It provided a framework for standardizing emissions data, which later shaped international reporting standards.

- It introduced refrigerant emissions into the climate risk conversation, leading to stricter policies on leak prevention and management.

What started as a voluntary reporting program at the DOE eventually paved the way for the mandatory disclosures and refrigerant regulations we see today. Businesses that once resisted emissions tracking now recognize it as a financial necessity—not just an environmental requirement.

The Turning Point for Refrigerant Regulations: From Ozone to Climate Change

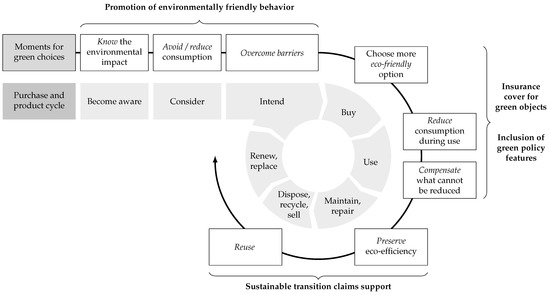

For more than 30 years, the refrigerant industry has been adapting, innovating, and preparing for change. Every refrigerant phaseout—from CFCs to HCFCs to HFCs—has followed the same pattern: regulations tighten, new solutions emerge, and the industry evolves.

But here’s the reality: None of this should be surprising.

The transition away from high-impact refrigerants has been in motion for decades. Companies that act shocked by today’s regulations are ignoring years of warnings, research, and industry-led advancements. Even if some disagree with the policies driving these changes, the shift away from high-GWP refrigerants is not just about government intervention—it’s about industry needs, technological progress, and market-driven efficiency.

The pivotal moment came in 2007, when the State of Massachusetts sued the EPA, arguing that greenhouse gases—including refrigerants—should be regulated under the Clean Air Act. The Supreme Court’s 2009 ruling forced the EPA to classify HFCs as pollutants, setting the stage for their phasedown under the AIM Act of 2020. But the truth is, the industry was already moving in this direction.

Manufacturers, retailers, and service providers weren’t waiting for regulations to act. They were investing in better leak detection, more efficient systems, and lower-GWP alternatives because it made financial and operational sense.

Three Principles That Have Endured Every Refrigerant Phaseout

Through every transition—CFCs to HCFCs, HCFCs to HFCs, and now HFCs to lower-GWP alternatives—the companies that have stayed ahead of the curve have always followed three fundamental strategies:

✔ Reduce Leaks – Every regulatory shift has emphasized preventing unnecessary refrigerant loss. Leak prevention lowers emissions, reduces energy waste, and minimizes compliance risks and replacement costs. [[link to cc site]]

✔ Improve Efficiency – Leaks force refrigeration systems to work harder, increasing energy costs and accelerating wear and tear. Optimizing system efficiency not only lowers expenses but also extends the lifespan of assets So learn how to react to inputs not just be overwhelmed by the data. [[ [[Bueno link on our page]]

✔ Plan for the Future – The most resilient companies don’t wait for the next phaseout to catch them off guard. They develop long-term refrigerant management strategies that account for system lifecycles, upcoming regulations, and emerging technologies—ensuring they remain compliant, cost-effective, and ahead of the competition.

This is the first of a 3 part series on refrigerant regulations, the histyory how we got here and more importantly how we get to where we need to be in order to deliver efficient, cold air where and when it is needed.

III. Why Traditional Financial Statements Hide Operational Waste

Traditional financial statements often fail to capture an organization’s operational waste and inefficiencies. This is because financial statements typically focus on financial metrics, such as revenue and expenses, rather than operational metrics, such as energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, organizations may not be aware of the operational waste and inefficiencies occurring within their operations, which can lead to unnecessary costs and environmental impacts.

For example, a company may use energy-inefficient equipment or processes that result in high energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. However, these costs may not be reflected in the company’s financial statements, making it difficult for the company to identify areas for improvement. By incorporating operational metrics into their financial statements, organizations can better understand their operational waste and inefficiencies and develop strategies to reduce them. This approach not only helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions but also cuts unnecessary costs, thereby improving overall operational efficiency.

IV. The Science of Refrigerant Leaks: Financial Impact & Efficiency Losses

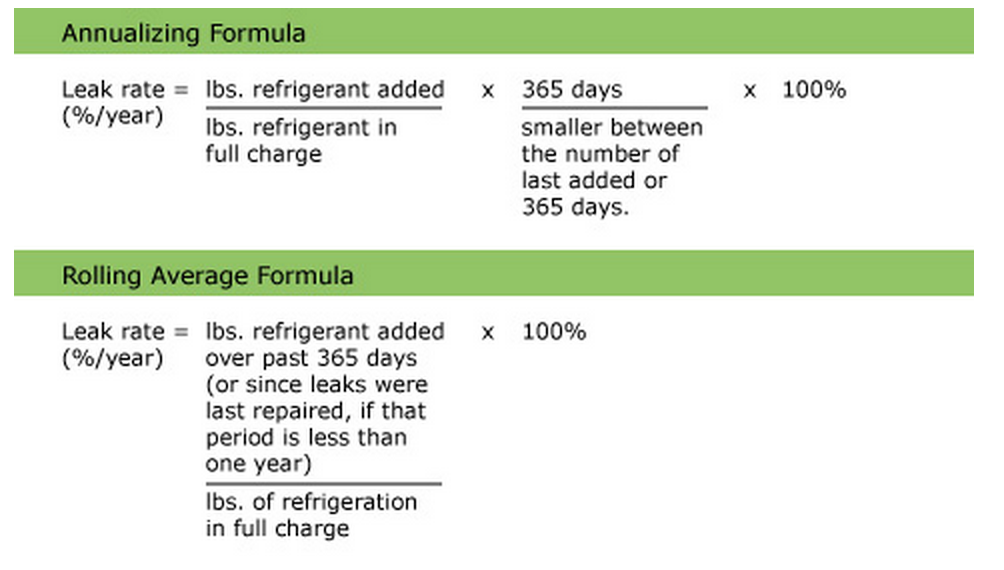

Refrigerant leaks are a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions and can have a substantial financial impact on organizations. Refrigerants are used in a wide range of applications, including air conditioning, refrigeration, and industrial processes. However, when refrigerants leak, they can release potent greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), into the atmosphere.

The financial impact of refrigerant leaks can be significant. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), they can result in energy efficiency losses of up to 20% and increase energy costs by up to 30%. Furthermore, they can cause equipment damage and downtime, which can lead to additional costs and lost productivity.

To mitigate the financial impact of refrigerant leaks, organizations can implement a range of strategies, including:

- Regular maintenance and inspection of refrigeration equipment: Ensuring that all equipment is regularly checked and maintained can prevent leaks and improve efficiency.

- Use of leak detection technologies: Advanced technologies can help detect leaks early, allowing for prompt repairs.

- Implementation of refrigerant management programs: Structured programs can help in tracking and managing refrigerant use and leaks.

- Use of energy-efficient equipment and processes: Investing in energy-efficient equipment can reduce the likelihood of leaks and improve overall efficiency.

By understanding the science of refrigerant leaks and implementing effective strategies to mitigate them, organizations can reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, improve their energy efficiency, and minimize their financial losses.

II. Why Traditional Financial Statements Hide Operational Waste

Most CFOs, investors, and executives rely on financial statements that don’t directly account for refrigerant leaks or emissions-related inefficiencies.

🔹 A 10% refrigerant leak increases energy costs by 20%—but financial reports simply show “higher OpEx.”🔹 Equipment running at 75% efficiency costs more in energy than replacing a failing seal—but that cost is buried in utility expenses.🔹 Technicians spend 30% of their time on preventable repairs—but labor costs appear stable, raising no alarms.

Emission factors are crucial values used to quantify greenhouse gas emissions based on activity data, such as fuel consumption and process emissions. These factors vary by fuel type and region and are essential for accurate and consistent calculations, often standardized by methodologies from reputable sources like the GHG Protocol.

📊 How Traditional Financial Statements Mask Operational Waste

| What’s Actually Happening | How It Appears in Financial Statements |

|---|---|

| A 10% refrigerant leak increases energy costs by 20%. | Higher OpEx—blamed on market conditions. |

| Aging HVAC systems run at 75% efficiency instead of 95%. | No clear indicator—costs hidden in utility bills. |

| Technicians spend 30% of their time on preventable repairs. | Labor costs appear stable—no red flags. |

📌 Key takeaway

The smartest businesses track refrigerant emissions and energy waste as closely as financial metrics—ensuring operational waste is corrected before it impacts profitability.

III. The Science of Refrigerant Leaks: Financial Impact & Efficiency Losses

🔬 Bostock & Kim’s research, alongside Purdue University findings, prove that even minor refrigerant leaks cause exponential cost increases.

Accurately calculating emissions from refrigerant leaks is crucial to understanding their financial impact. This involves applying specific emissions factors based on fuel consumption data to compute CO₂ equivalents, providing a comprehensive view of an organization’s carbon footprint and Scope 1 emissions.

📊 Leak Rates and Energy Cost Impact

| Leak Rate | Energy Cost Increase | Operational Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1% leak | 1% higher energy use | Small inefficiencies add up over time. |

| 10% leak | 10% higher energy use | Costs become noticeable but are ignored in financial reports. |

| 20% leak | 25% higher energy use | Now regulators and investors take notice—too late. |

🔎 Example: A Supermarket Chain’s Refrigerant ProblemA 10% refrigerant leak across 500 stores added $25 million in extra energy costs annually—but it never showed up in financial reports as a specific issue.

📌 Key takeaway

The best-run businesses don’t wait for regulations to force action—they fix inefficiencies before they escalate into financial and legal liabilities.

IV. The Labor Shortage: Why Regulations Help Define Efficiency Boundaries

The HVAC and refrigeration industry is facing a severe labor shortage, and inefficient refrigerant management increases the burden on an already stretched workforce. Indirect GHG emissions, specifically categorized as Scope 2 emissions, relate to the greenhouse gases produced when purchasing electricity, steam, heat, or cooling. Identifying these sources of emissions is crucial, as organizations indirectly influence them in their value chains.

📉 Industry Challenges:

✔ 50,000 HVAC technicians retire annually, but only 30,000 new workers enter the field.

✔ Emergency repair calls cost 30%+ more than scheduled maintenance.

✔ Data centers and grocery chains report 2x longer repair wait times due to technician shortages.

We are on a mission to redefine refrigerant leak detection.

How Regulations Reduce Labor Strain

✔ ISO 14001 mandates preventative leak detection policies, reducing emergency repair demand.

✔ SEC and CSDDD force companies to standardize emissions reporting, ensuring maintenance teams focus on efficiency rather than compliance panic. Emissions factors are standardized values that quantify the amount of greenhouse gases emitted per unit of various activities, such as energy consumption and fuel usage. These factors vary based on different energy sources and processes and are essential for calculating emissions across different scopes of reporting.

✔ Data-driven emissions tracking reduces technician workload—fewer leaks mean fewer emergency repairs.

📌 Key takeaway

The best companies use regulations to streamline workforce efficiency, rather than reacting to compliance deadlines.

V. Spotting Red Flags: How Investors & Operators Can Identify High-Risk Companies and Fugitive Emissions

🚨 Red Flags in Financial & Emissions Reports

| Red Flag | What It Means | Investor Risk |

|---|---|---|

| ❌ “No refrigerant leaks reported” | They aren’t tracking leaks properly. | Higher OpEx in the future. |

| ❌ Energy costs rising, but sustainability claims stay the same | The company is likely greenwashing. | Shareholder lawsuits, SEC scrutiny. |

| ❌ No clear emissions data in reports | Likely non-compliant with SEC & EU regulations. | Legal penalties, loss of investor confidence. |

📌 Key takeaway

Investors and CFOs must demand emissions transparency—just like they do for financial audits.

Final Takeaway: Regulations Are a Safety Net—Operational Excellence Comes First

✔ Regulations exist because businesses overlook inefficiencies in financial reports, leaving someone exposed to risk. More often than not, that “someone” is a financial institution or insurer—not a stockholder, who is typically too distant from daily operations to recognize the risks early.

✔ The best companies don’t wait for regulations to set the boundary—they move it themselves. Staying ahead of compliance ensures better efficiency, cost control, and long-term stability.

✔ Tracking emissions isn’t just about compliance—it’s a financial strategy. Businesses that actively monitor and reduce refrigerant leaks save money, improve efficiency, and gain a competitive advantage.

🔎 Would You Invest in a Business That Hid Its Biggest Costs?

A company that ignores refrigerant emissions is like one that ignores its balance sheet—eventually, the hidden costs will come due.

💡 The smartest businesses don’t just follow regulations—they lead in efficiency.